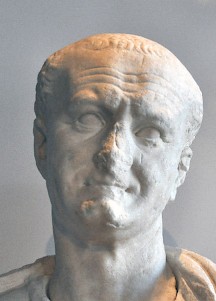

Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus

Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus (c.14-69): Roman senator, commander of the Rhine army during the Batavian revolt. His reputation has suffered severely from the biased description of his campaigns in the Rhineland by the Roman historian Tacitus.

A large part of the life of Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus is unknown to us. His father, who lived near Naples, had been procurator of the imperial domains in Gallia Narbonensis during the reign of Tiberius. Procurators were usually nouveaux riches, wealthy people who did not have the personal dignity that would made them acceptable as knight or senator. You had to have old money for that.

Nevertheless, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus reached the highest of all senatorial offices, the consulate (47). Swift upward social mobility was possible only with support from the emperor, but we do not know why, when, and from whom which Hordeonius received it.

Because the consulship was held after one's thirty-third birthday, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus was born in 14 CE, or earlier. He must have been governor of a minor province, and when he finally becomes "visible" in our sources at the beginning of the year 69, he is governor of Germania Superior, the country along the upper Rhine. This was a very responsible task, because in this region, four legions guarded the border. However,

the army despised its commander-in-chief. Elderly and lame, Flaccus lacked personality and prestige. Even when the troops were quiet, he was unable to maintain discipline; and by the same token, if the men were in an ugly mood, his feeble attempts to control them merely added fuel to the flames.note

The author of these words is the Roman historian Tacitus. In his description of the revolt of the Batavians, which was to occupy all of Flaccus' attention in the last half year of his life, he strongly focuses on the opposition between on the one hand civilization and decadence and on the other hand barbarism and vitality. These two poles are represented by Flaccus, who is portrayed as weak and incapable, and the energetic Batavian leader Julius Civilis. The result is something of a black legend in which Flaccus embodies every possible Roman vice.

Tacitus was not the first one to defame Flaccus. As we will see in this article, the Batavian insurrection could have been prevented if the Roman emperor Vitellius had not been forced to fight against the rebel Vespasian, and the latter had not encouraged the Batavians to revolt. However, Vespasian won the civil war, and he needed a scape-goat to distract the attention from his own responsibility. Flaccus, the son of a nobody, was the perfect victim. Tacitus, who owed the beginning of his career to Vespasian and its progress to his sons Titus and Domitian, had no problems to accept their version of the truth.

So, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus was governor of Germania Superior. He succeeded Lucius Verginius Rufus, who had suppressed the revolt of the governor of one of the Gallic provinces, Julius Vindex, who had decided to terminate the oppression of Nero, and had started to search for a worthy successor. In April 68, he found his man, Servius Sulpicius Galba, and started an insurrection. Verginius and the Rhine army made quick work of the revolt. However, Nero had committed suicide, and Galba started to reign. One of his first acts was to have Verginius replaced by Flaccus.

The armies of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior thought that Galba distrusted them, and they decided to revolt. Their favorite was the governor of Germania Inferior, Aulus Vitellius. It is extremely likely (but cannot be proven) that Flaccus knew in advance of the plans of his soldiers. Vitellius took more than half of the soldiers of the Rhine army with him when he marched on Rome, leaving behind only a small garrison to guard the border with "free" Germania. A new governor of Germania Inferior was not appointed, and Flaccus was placed in charge of both Germanic provinces and eight incomplete legions.

Vitellius' rebellion was successful. When Galba heard of the insurrection, he panicked, provoked powerful men, and was lynched on the Forum Romanum. The Senate now recognized Marcus Salvius Otho as emperor. He inherited the war against Vitellius, was defeated at Cremona (April 69), and committed suicide. Now that Vitellius was master of the empire, he immediately sent back troops to the vulnerable Rhine border.

However, the Roman empire was not to return to normalcy yet. In July, the commander of the Roman forces in Judaea, Vespasian, was proclaimed emperor. Immediately, Vitellius ordered the retutn of his troops, and demanded extra soldiers to be sent to Italy. This was the beginning of great troubles in the north.

Flaccus refused to sent soldiers away from the Rhine, because he knew that something was going on among the Batavians, and thought that he was to need all available men. He had already sent soldiers of the Eighth legion Augusta from Novae in Moesia (modern Svishtov in Bulgaria) to Nijmegen, the main Roman base in the country of the Batavians.

This is not mentioned by Tacitus, but has been proven by archaeologists who were excavating the Kops Plateau at Nijmegen (Netherlands), the camp of an auxiliary cavalry unit. They found a small silver medal that mentioned a centurio named Gaius Aquillius Proculus, who is identical to a Roman officer who played an important role in the initial stages of the Batavian revolt. The medal states that Aquillius belonged to the eighth legion, which proves that Flaccus sent reinforcements and understood what was going to happen.

However, Vitellius issued a second order: there would be forced recruitments among the suspected rebels. This measure was meant as a deterrent to future insurrectionists and might have worked, but no Batavian was impressed. After all, there were no Romans troops left to implement the threat.

Nor were the Batavians the sort of people that were easily impressed. They were one of the poorest tribes in the Roman empire, living in the river area of what is now called the Netherlands, which was in Antiquity simply called the Island (between the rivers Rhine and Maas). The Roman tax gatherer had little to gather in this region, and therefore, the Batavians had to give soldiers to Rome. They were well-trained, formidable warriors.

The only result of the forced recruitments was, therefore, that in August 69, the Dutch river area changed into a war zone. The above-mentioned Aquillius was able to regroup the auxiliary units that happened to be present, but this army was defeated on its way to the safety of the legionary base at Xanten.

The leader of the Batavian revolt was Julius Civilis, a good commander and a brilliant diplomat. When asked what he was fighting for, he said that he was supporting Vespasian (whom he knew from the British wars where they had both been fighting). He could indeed show a letter in which Vespasian had invited him to revolt, which would cause great difficulties for Vitellius.

Flaccus did not know what to make of this. Was he facing a local insurrection (which ought to be suppressed as soon as possible) or was he fighting a civil war (in which case success would be dangerous if Vespasian became emperor)? In other words, he was to fight with his arms bound. It was an impossible situation.