Traiectum ad Mosam (Maastricht)

Q1924295Traiectum ad Mosam was a middle-sized village near the place where the main road between Tongeren, the capital of the Tungri, and Cologne, the capital of the Ubians and Germania Inferior, crossed the Meuse. In the fourth century, the town, which served as port of Tongeren, was heavily fortified and this castle became the nucleus of the medieval and modern city.

The history of Roman Maastricht, which perhaps was called Traiectum ad Mosam ("ford in the Meuse"),note is the story of a bridge. When the Romans started to develop northern Gaul, they paved an already existing road to connect the capitals of the Nervii and Tungri, Bavay and Tongeren, with the capital of the Ubians, Cologne.

The tens of thousands of inhabitants of Cologne lived in one of the most important cities north of the Alps. Situated on the Rhine frontier, this center of Roman culture was the residence of the governor of the military zone and a giant port of transshipment. The soldiers in the frontier forts needed food, especially corn, which was produced on the fertile loess of northern Gaul. Therefore, the road from Bavay to Tongeren to Cologne was of vital importance for the survival of the army of the Lower Rhine.

The course of the ancient, gravelled road can still be followed in today's Maastricht. The western part of the ancient main road followed the course of the modern Tongerseweg. A visitor would have known that he was approaching a town when he saw the cemetery along the road, which has been discovered under the Vrijthof (the name of this square means "cemetery"). Here, the road made a turn to the right, through what is now the Havenstraat. It is known that an apothecary and a cobbler had their shops in this street. At the end of the ancient Havenstraat was a sanctuary, on the site of the later, medieval church of Our Lady Star of the Sea. Now, the road turned to the left, and through the modern Plankstraat, the visitor arrived at the river Meuse, which he had to cross if he wanted to proceed to Cologne.

To facilitate transport across the irregular Meuse, a bridge was built. Dendrochronological research of the foundation of the piers has shown that the monument was rebuilt several times, but it has not yet been possible to establish the date of the first building phase. It is certain, however, that it existed in the third quarter of the first century CE, because it is mentioned in the description of the Batavian revolt as the place where the rebel leader Julius Civilis defeated his opponent Claudius Labeo (70).

It is tempting to accept the existence of an older (pontoon) bridge. The oldest buildings of Bavay and Tongeren can be dated to 30-20 BCE, and the foundation of Cologne to 37 or 19. Six years later, the army of the Lower Rhine consisted of no less than five legions, and we can assume that the road was already of very great importance. There must have been a bridge across the Meuse. Perhaps it was built by general Drusus, who was the first to organize the Rhine frontier and is known to have ordered several other large construction works.

Maastricht was not a new town, although the archaeological evidence for prehistoric settlement is meager. However, what we have is intriguing. Under the modern Hotel Derlon, traces of very old pavement have been discovered. It antedates a later Roman building, and although it is impossible to give a more precise date to the pavement, it suggests a venerable old age. No less intriguing is the existence of a large fortress at Kanne-Caster to the south of Maastricht, which was built by the native population in c.31 BCE. Obviously, there must have been something in the neighborhood to guard. Unfortunately, this is about everything we know about the pre-Roman town.

We may speculate, however, that there was a religious shrine. The native population of the Low Countries often built temples on the confluence of two rivers, and we know for certain that in the Roman age, there was a sanctuary near the confluence of the Meuse and the Jeker, a small river that connects Tongeren and Maastricht. The remains of the sacred precinct were discovered under Hotel Derlon; the temple itself must have been, as we already noticed, under the modern basilica of Our Lady.

The propylaea of the Roman sanctuary, which were built in c.100 CE, were to the north in a wall that was some 18 meters wide. In the last quarter of the second century, a large column was erected inside the sacred precinct, which was dedicated to the supreme god Jupiter. Only a few fragments remain, but comparison with similar monuments (e.g. the column from Mainz) allows us to make a reliable reconstruction.

To the north of this sanctuary was a bathhouse, also built after 100. Although several building phases have been recognized, it is not clear when it was built. There must have been inns and taverns in the neighborhood, where visitors from Bavay and Tongeren and bargemen could meet - after they had done their religious duty in the sanctuary, of course. It is reasonable to suppose that there was a police station near the river port, but neither the station nor the port have been discovered.

So this was Roman Maastricht: a flourishing mercantile town near an important bridge. Unfortunately, the bridge was of great strategic importance and this made Maastricht a natural target in times of war. We have already seen that there was a battle near Maastricht during the Batavian revolt. Two centuries later, in 275, the Germanic Franks invaded Germania Inferior and sacked Maastricht.

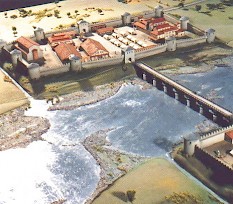

However, the town was not fully abandoned, and the emperor Constantine I the Great (306-337) ordered the construction of new, massive walls. The former sanctuary was partly demolished and the stones were reused in the walls of the new castle. The bridge across the Meuse was rebuilt in 333.

The new fort was 170 meters long and 90 meters wide. The walls were 1½ meters wide and may have been 4 to 5 meters high. There must have been ten round towers and two gates. Outside the walls was a large moat. There must have been a similar settlement on the east bank of the Meuse (it would be odd to defend the bridge on only one side of the river), but no remains of this part of late Roman Maastricht have been discovered.

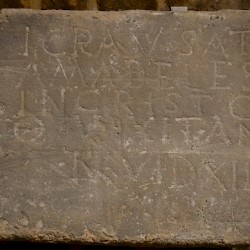

Excavations in the center of the fourth-century castle have shown the presence of a granary and several other, unidentified buildings (on the site of the ancient bathhouse). To the south of the granary, bishop Servatius of Tongeren built a Christian chapel over an old sanctuary, which was to become the basilica of Our Lady Star of the Sea. Natural stone from the Roman period has been reused when this church was rected. As we have already seen, this is one of the most sacred and beloved places in the Low Countries, and excavation will prove to be difficult.

The heavy walls of the fourth-century castle, the chapel of Servatius and his tomb to the northwest became the center of the Medieval town. In c.560, a magnum templum ("big church") was erected on the site of Servatius' grave.note This church and the church in the ancient fort were rebuilt in the eleventh century, and dominate the town until the present day. The walls of the castle were still in use in the ninth century; the bridge collapsed in the thirteenth century.

Museum

The excellent archaeological department of the Bonnefantenmuseum, which contained one of the most important archaeological collections of the Netherlands, was closed several years ago. Parts of the collections can be seen in the Centre Céramique. There is a nice view on some Roman ruins in the Museum Cellar of Hotel Derlon.