Satala (Sadak)

Q2211116Satala: (modern Sadak): Roman legionary base, used by XVI Flavia Firma and XV Apollinaris.

I am not betraying a big secret if I say that the site of the legionary fortress of Satala, east of modern Sadak, is not Turkey's most spectacular archaeological monument. There are no beautiful statues, there are - with one exception - no impressive buildings, and there are not even small architectural remains. Satala is simply not worth a detour, unless you're a specialist and can appreciate a field full of sherds and stones.

The exception that proves the rule is the ancient aqueduct, of which one arch and three piers survive. That's all there is. All this being said, however, the Roman fortresses may in the not too distant future become one of Turkey's most interesting excavations, if only because legionary bases are a rare type of military settlement - if only because Rome had only thirty legions. Turkey used to have four legionary bases, but three of them were swallowed in the storage reservoirs that were recently created in the Euphrates.

When the emperor Vespasian added Commagene to the Roman empire (72 CE), the upper Euphrates became a frontier zone; across the river were the Parthian Empire and the buffer state Armenia. The main road along the Roman border (limes) was from Trapezus on the shores of the Black Sea to Alexandria near Issus, Seleucia, and Antioch near the Mediterranean in the south. The legionary bases along this highway were Satala (for the recently founded Sixteenth Legion Flavia Firma), Melitene (XII Fulminata), Samosata (VI Ferrata), and Zeugma (IIII Scythica). Satala was chosen because it commanded not only the Euphrates, but also the road from central Anatolia to Armenia (essentially the modern E88/E80).

We would like to know more about the original settlement, but it will be hard to reconstruct it, because the site was destroyed in the mid-third century by troops of the Persian Sasanians (who had replaced the Parthians after 224), and was rebuilt several times. What can be seen today, belongs to the sixth-century reconstruction by the emperor Justinian (r.527-565). The circuit of the walls is too small to offer accommodation to a first- or second-century legion. The original military settlement is still lost.

Maybe, however, it was not on the site that now attracts visitors, but in the valley. As this photo shows, the aqueduct is lower than the sixth-century settlement, which proves that there was a bathhouse or a similar structure below the military base. On the other hand, bathhouses outside a fort are not unheard of (e.g., Schwäbisch Gmünd-Schirenhof). Until archaeologists have started to investigate Satala, we have insufficient knowledge of the first building phases.

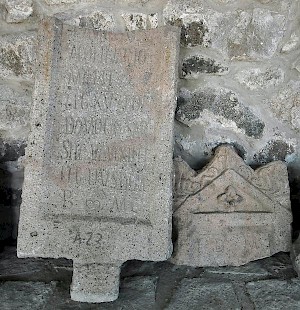

According to the Greek-Roman historian Cassius Dio, the emperor Trajan visited Satala during his war against the Armenians and Parthians (115-117) and received some vassal leaders.note During this conflict, which started successfully for the Romans but ended in a retreat from the conquered territories, the Sixteenth legion Flavia appears to have been replaced by XV Apollinaris. This can be deduced from the Roman tombstones that were found in the neighborhood. During the reign of Hadrian, this unit, together with XII Fulminata, was employed by Arrian (who was to become famous as biographer of Alexander the Great) in his campaign against the Alans.

After the conquest of Mesopotamia by Septimius Severus in the last decade of the second century, Satala was still a front city, but the Armenian province across the Euphrates, the district known as Sophene, posed no direct military threat. However, occupation of this site remained vital, because Satala still was the main connection between the river and the Black Sea. This also explains why the Sasanian king Shapur attacked the fortress in 252 or 256. He was successful.

It is certain that the fortress was rebuilt and reoccupied by XV Apollinaris, although the inscription known as CIL 2.13630 (more...) refers to building activities by another unit, II Armeniaca. The date of this legion's activities cannot be determined. The area remained contested by the Romans and Sasanians; in 298(?), Galerius assembled an army over here, marched east, and defeated Narseh's Persian armies at a place called Osxay.

Hardly anything is known about Satala's civil settlement, although it is certain that in the fourth century, there was a Christian community. A bishop from Satala named Euethius was one of those who signed the Acts of the First Oecumenical Council at Nicaea (325). A successor with the remarkable Germanic name Elfridius is recorded in 360.

The site was fortified again in 529 by the emperor Justinian. His courtier Procopius writes:

The city of Satala had been in a precarious state in ancient times. For it is situated not far from the land of the enemy and it also lies in a low-lying plain and is dominated by many hills which tower around it, and for this reason it stood in need of circuit-walls which would defy attack. Nevertheless, even though its surroundings were of such a nature as this, its defenses were in a perilous condition, having been carelessly constructed with bad workmanship in the beginning, and with the long passage of time the masonry had everywhere collapsed. But the Emperor tore all this down and built there a new circuit wall, so high that it seemed to overtop the hills around it, and of a thickness sufficient to ensure the safety of its towering mass. And he set up admirable outworks on all sides and so struck terror into the hearts of the enemy.note

This fortress survived for almost a century, but was eventually captured and destroyed in 607/608 by the Sasanian king Khusrau II the Victorious (r.590-628).

Today, the site is just waiting to become one of Turkey's main military monuments from the Roman period. In 2004, geophysical investigations took place, and a Swedish visitor reportedly found a bust in 2006. For the moment, however, it's not yet worth a detour.

Still, if you happen to be traveling from Erzincan to Kelkit, you may enjoy the weird landscape and leave the road for a brief visit. If you arrive from the south, a road sign near an empty patrol station will be your guide; if you arrive from the north, it's three kilometer after Mahomatli.