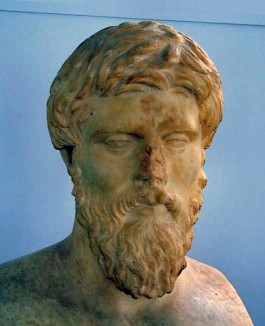

Plutarch

Plutarch of Chaeronea (46-c.122): influential Greek philosopher and author, well known for his biographies and his moral treatises.

It is not overstated to say that, together with Augustine of Hippo and Aristotle of Stagira, Plutarch of Chaeronea is the most influential ancient philosopher. He may lack the profundity of Augustine, the most influential philosopher in the early Middle Ages, and the acumen of Aristotle, considered the master of all intellectuals of the late Middle Ages, but the Sage of Chaeronea is an excellent writer and from the Renaissance to the present day, his moral treatises have found a larger audience than any other ancient philosopher. In his own age, he was immensely popular because he was able to explain philosophical discussions to non-philosophical readers, Greek and Roman alike. The fact that he was priest in Delphi will no doubt have improved his popularity.

Life

Plutarch was probably born in 46 in the Boeotian town Chaeronea. His parents were wealthy people, and after 67, their son was able to study philosophy, rhetorics, and mathematics at the platonic Academy of Athens. However, Plutarch never became a platonic puritan, but always remained open to influences from other philosophical schools, such as the Stoa and the school of Aristotle. It is likely that the young man was present when the emperor Nero, who visited Greece at this time, declared the Greek towns to be free and autonomous.

Because Plutarch was a rich man, he became one of the leading citizens of Chaeronea and he is known to have represented his town on several occasions. For example, he visited the governor of Achaea, and traveled to Alexandria and Rome (several times). Again, this proves that he was a rich man.

Among his friends was Lucius Mestrius Florus, a consul during the reign of Vespasian, and Plutarch's guide during his visit to Cremona, where two important battles had been fought in 69, the year of the four emperors Galba, Vitellius, Otho, and Vespasian. Mestrius also secured the Roman citizenship for Plutarch, whose official name now became Mestrius Plutarchus. At the end of his life, he was honored with the procuratorship of Achaea, an important office that he probably held only in name. His involvement in the Roman world, although from a carefully maintained distance, explains why he shows so much interest in the history of Rome. Nevertheless, he was slow to learn Latin.note

In the 90s, Plutarch, who had seen much of the world, settled in his home town. When asked to explain his return to the province, he said that Chaeronea was in decline and that it would be even smaller if he did not settle there. For some time, he was mayor.

In his treatise Should Old Men Take Part in Politics?, Plutarch tells us that he occupied an office in the holy city Delphi, and he is known to have become one of the two permanent priests, responsible for the interpretation of the inspired utterances of the Pythia, the prophetess of Delphi. In these years, a library was built near the sanctuary, and it is tempting to assume that Plutarch was behind this initiative.

In the two first decades of the second century, he studied and wrote many books. According to an incomplete third-century catalogue, there were between 200 and 300 titles. These books brought him international fame, and the home of the famous author became a private school for young philosophers. He was often visited by Greeks and Romans, although not necessarily to study philosophy. The emperor Trajan may have been one of the visitors (winter 113/114?), and it may have been on this occasion that Trajan honored Plutarch with the ornaments of a consul, an important award. From now on, Plutarch was allowed to wear a golden ring and a white toga with a border made of purple.

Plutarch died after his procuratorship, which was in 119, and before 125. The year 122 is just guesswork. The Delphians and Chaeroneans ordered statues to be erected for their famous citizen.

In the Consolation to his wife, Plutarch mentions four sons and we know that at least two survived childhood. It has often been remarked that in his many publications, Plutarch shows that he was devoted to his parents, grandfather, brothers, his wife Timoxena, and to their children, but this is of course an impression that every author wants to convey.

The Moralia

Plutarch's oeuvre can be divided into two parts: the biographies (below) and the remainder, which is usually called the Moralia or Moral Writings. This second group is a varied collection of literary criticism, declamations, ethical essays, advice, polemics, political writing, conversation and consolation. Although there is much variation among these treatises, it is clear that its author aimed at the moral education of his readers (e.g. in works with titles like Checking Anger, The Art of Listening, How to Know Whether One Progresses to Virtue).

Plutarch's central theme seems to have been his idea that there was a dualistic opposition between the good and evil principles in the world. Later philosophers of the neoplatonic school disagreed with this idea, and this explains why several of Plutarch's more serious philosophical publications are now lost. What we have left, is generally lighter work, together with his attacks on the Stoa and Epicurism.

They are interesting texts, because they show a very pragmatic philosopher, whose aim it is to make people more virtuous and therefore happier. In fact, several works have a striking resemblance to modern "do it yourself"-books of social psychology. Treatises like the Advice to Bride and Groom may strike us as conservative and anti-feminist, but in Antiquity, the counsels may indeed have been helpful.

The biographies

Plutarch's biographies, dedicated to Quintus Socius Senecio, are in fact moral treatises too. He describes the careers of a Greek and a Roman, and compares them - an idea Plutarch copied from Cornelius Nepos. For example, in the Life of Theseus/Life of Romulus, he describes the lives of the founders of Athens and Rome, and in a brief epilogue penetrates into their respective characters. Another example is the comparison of Themistocles and Camillus, an Athenian and a Roman who were both sent into exile. The result is not only an entertaining biography, but also a better understanding of a morally exemplary person, which the reader can use for his own moral improvement.

A good example of Plutarch's method is his Life of Alexander/Life of Julius Caesar, in which he gives a very short summary of his biographical ideal.

It is not histories I am writing, but lives; and in the most glorious deeds there is not always an indication of virtue of vice, indeed a small thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of a character than battles where thousands die.note

This is a good description of what Plutarch has to offer. He will not give an in-depth comparative analysis of the causes of the fall of the Achaemenid empire and the Roman Republic, but offers anecdotes with a moral pointe. We should read his Life of Alexander as a collection of short stories, in which virtues and vices are shown. The most important theme (one might say: Plutarch's vision on Alexander's significance in world history) is that he brought civilization to the barbarians and made them human; Alexander is, so to speak, a practical philosopher, who improves mankind in a rather unusual but effective way. This theme is more explicitly worked out in a writing called The Fortune and Virtue of Alexander (text).

Because Plutarch's moral judgment is more important than his historical judgment, he sometimes makes odd errors (e.g., praising Pompey's trustworthy character and tactful behavior), but he is not a bad historian. For example, unlike his Roman contemporary Suetonius, he sums up all his moral anecdotes in a more or less chronological sequence. (Suetonius does not adhere to this principle.) To return to Alexander: most authors of books on the Macedonian king took their material from either the 'vulgate' tradition (which follows a biographer called Cleitarchus) or from the 'good' tradition (which follows Ptolemy, one of Alexander's generals). Plutarch, on the other hand, tells his own, moral story and takes elements from both traditions.

If the reader of this article has the impression that Plutarch is a boring moralist, he is mistaken. Plutarch's sincere interest in his subjects as human beings makes the Lives very readable and explains why they have found so many readers - both ancient and modern. The ultimate tribute to Plutarch was paid by a twelfth-century official of the Byzantine church, John Mauropos, who prayed that on the Day of Judgment, when all non-Christians would be sent to hell, God would save the soul of the Sage of Chaeronea.