Via Egnatia

Q273783Via Egnatia: Roman road from the Adriatic Sea to Constantinople, passing through what is now called Albania, Northern Macedonia, Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

The Via Egnatia was built by a Roman senator named Gnaeus Egnatius, who served as praetor with the powers of proconsul in the newly conquered province of Macedonia in the late 140s BCE. A milestone found near the place where the Via Egnatia crossed the Gallikos River, just west of Thessaloniki, is evidence for his activities. The bilingual inscription, now in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, correctly records a distance of 260 miles to Dyrrhachium (modern Dürres), the port on the Adriatic Sea where the road started.note

The course of the road is described by Strabo, who is quoting from Polybius' World History (which proves that this part of the road was finished prior to the historian's death in c.118).

Although the road as a whole is called the Egnatian Road, the first part of it is called the Road to Candavia (an Illyrian mountain) and passes through the city of Lychnidus [mod. Ohrid] and Pylon, a place on the road which marks the boundary between the Illyrian country and Macedonia. From Pylon the road runs to Barnus through Heracleia [mod. Bitola] and the country of the Lyncestae and that of the Eordi into Edessa and Pella and as far as Thessalonica.note

East of Thessalonica, the road continued to Amphipolis, Philippi, Neapolis, and Kypsela on the Hebros. Cicero' speech On the consular provinces 4 proves that before 56 BCE, the road had been extended through southern Thrace to the Hellespont, where it would continue to Perinthus and Byzantium. The total length of the road must have been about 1120 kilometers. After Byzantium had become the capital of the eastern half of the Roman Empire, a special gate was made for the Via Egnatia, called the Golden Gate. It was used for the triumphal entries of the Byzantine emperors.

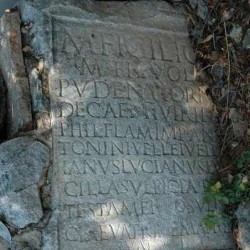

Like all Roman roads, the pavement of the Via Egnatia was about six meters wide. In Philippi, large tracts survive. The road passed along the central market, and a sewer made sure that the street was never too wet or dirty. It was repaired several times; on one place, you can still see that old tombstones and honorific inscriptions were reused. In other cities, the Via Egnatia must have been more or less similar.

The road was very important. Connecting the eastern and western part of a once powerful state, the Macedonian kings had already built a road from the Adriatic to the Aegean Sea. For the Romans, it was essentially the continuation of the Via Appia: anyone coming from Rome and travelling to the east, would come to Brundisium, cross the Adriatic, reach Dyrrhachium (or Apollonia), and continue along the Via Egnatia.

It was used in 84 BCE by the armies of Sulla, who was chasing Mithridates VI Eupator;note in the winter of 49/48, Caesar and Pompey fought over control of the road at Dyrrhachium; Mark Antony and Octavian defeated Brutus and Cassius at Philippi, both armies using the same road. A more peaceful user was the apostle Paul, who visited Neapolis, Philippi, Amhipolis, and Thessalonica.note

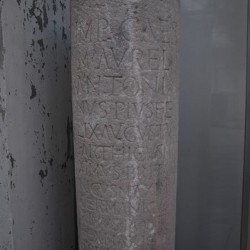

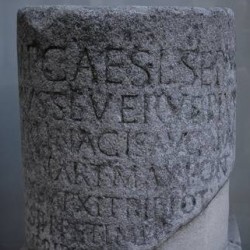

The milestones along the road are evidence that repairs took place during the reigns of Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, and Septimius Severus - three emperors who waged wars against the Parthians and needed good lines of contact. According to Procopius, the road was repaired by the emperor Justinian in the sixth century:note it may have had something to do with the wars against the Persians in the east and Ostrogoths in the west.

The road from Constantinople to Thessalonica was still important during the Byzantine age: merchants, soldiers, and monks were among the travellers, and it is interesting to notice that in the age of the Crusades, Bogomilism (a kind of Manicheism) spread from the East to the West along the Via Egnatia. The first missionaries were Slavonic speaking missionaries; later, the knights of the Fourth Crusade returned to the Languedoc with dualist beliefs.

Literature

- M. Fasolo, La via Egnatia I. Da Apollonia e Dyrrachium ad Herakleia Lynkestidos (1976)

- F. O'Sullivan, The Egnatian Way (1972)