Cornelis de Bruijn

Cornelis de Bruijn (c.1652-1727) was a Dutch artist and traveler. He is best known for his drawings of the ruins of Persepolis, the first reliable pictures of these palaces to be accessible for western scholars. His other visits included the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, Jerusalem, Russia, and the East Indies.

Syria, Turkey, Italy

In Tripoli, the house of the Dutch consul was De Bruijn's residence for four months, but he made a few tours. One of these brought him to the Lebanon, where he admired the famous cedar trees, and on a second, he reached Acre, Nazareth, Lake Kinneret, and Mount Tabor. On his return, he visited Tyre again, called at Sidon, said good-bye to Tripoli, and continued to Aleppo, where he was living in the caravanserai from May 1682 to April 1683. In his account, he tells about the Roman coins he bought on the market, which he describes in great detail.

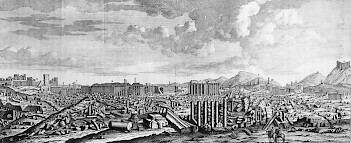

From Aleppo, De Bruijn wanted to travel to the recently identified ruins of Palmyra, a once famous center of the caravan trade between the Roman and Sasanian empires. Five years before, the remains of the old town had been visited by a group of Englishmen, and the Dutch artist wanted to see the site too. Unfortunately, a local tribe of Bedouins refused to cooperate, and De Bruijn left Aleppo, slightly disappointed.

Still, the reader of Travels in the Principal Parts of Asia Minor does not have to share in this disappointment. Eight years after De Bruijn's attempt, the reverend William Halifax and a Dutchman named G. Hofstede van Essen had more success, and De Bruijn offered his readers a summary of what Halifax had written, with some minor additions. He also added an engraving, which is a copy of a large painting by Hofstede, as we will see below.

De Bruijn left Syria from the port of Alexandretta (modern Iskenderun), briefly visited Cyprus, and in the first half of June he traveled from Antalya to Smyrna, an unusual inland route that was known to be dangerous. The main peril, however, was not robbery, but a large snake, which forced De Bruijn to use his pistol.

Safe and healthy, he arrived in Smyrna, and was to remain in this Greek city for another sixteen months. Only now did he discover that during his former visits, the Dutch consul in Smyrna and the ambassador in Constantinople had believed that De Bruijn was the would-be assassin of Johan de Witt. When the artist finally left Smyrna, on 25 October 1684, he had been away from home for more than ten years.

On 10 November 1684, he arrived in Venice, where he was to stay until 1692 at the studio of a Bavarian painter whose real name was Johann Karl Loth, although every Italian called him Carlotto (1632-1698). De Bruijn is mentioned as one of Loth's students, but this does not mean very much. In this age, the old ranks of artisans ("student", "bachelor", and "master") were just titles: economics of scale forced workplaces to keep many people on the rank of student and bachelor, which was cheaper. That De Bruijn is called a student of Loth, only means that he was on his payroll. In fact, he was a professional, and when he returned to The Hague, he was almost immediately recognized as a master.

Hardly anything is known about De Bruijn's Venetian years, and it is possible that an investigation of the archives of Venice will be fruitful. He must have met Johann Michael Rottmayr (1656-1730), who was also employed by Loth and would one day be famous. Of course De Bruijn must have heard how in 1688, William of Orangenote had accepted a rather dubious invitation to become king of England, had defeated the regular army, had conquered London, had become king, and had announced that he, as he was accustomed in Holland, would share power with the Parliament. The story of the "glorious revolution" must have fascinated De Bruijn, because William had risen to power after a murder of which the artist was still suspected.

It is possible that De Bruijn contributed to the one work from the Loth studio that can be dated to these years, a copy of Titian's Death of Peter of Verona. The original used to be in Venice's San Zanipolo but is now lost.

In 1692, Loth was called to Vienna to be made court painter of the emperor Leopold I. Johann Karl Loth would occupy this honorable position until his death, and was succeeded by Rottmayr. Not being a Catholic, De Bruijn could not follow his colleagues to the imperial court, and instead returned home. The Rhineland was no longer a war zone, and he could visit Frankfurt and Cologne, where he spent some time and celebrated Christmas, New Year, Epiphany (the three wise men are said to be buried in Cologne), and the famous Carnival. On the fourteenth of March 1693, he arrived in Amsterdam; five days later, he was in The Hague.