Pliny the Younger (6)

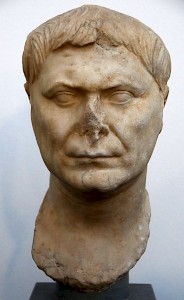

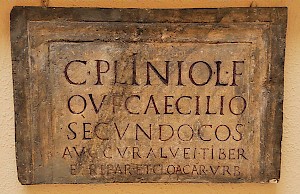

Pliny the Younger or Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (62-c.115): Roman senator, nephew of Pliny the Elder, governor of Bithynia-Pontus (109-111), author of a famous collection of letters.

Although Pliny had not occupied a public function for a couple of years, Trajan had not forgotten the man from Como. Not only was Pliny's name on everybody's lips -at least on the lips of those who were literary minded- but he had made himself even better known in two famous lawsuits.

Pliny had already secured the conviction of corrupt governors of Baetica and Africa, and in 101 the inhabitants of Baetica had approached him with the request to prosecute Caecilius Classicus. The man died shortly before the trial, and it was widely believed that he had committed suicide. However, the Baeticans continued their case and the Senate convicted the dead governor.

The other case involved a man named Julius Bassus, former governor of Bithynia-Pontus (the north of modern Turkey). In 102 or 103, he was accused of extortion, although he himself said that he had merely accepted presents. He was clearly guilty, because it was not permitted to accept gifts. This time, Pliny pleaded for the accused, who was discharged. It was Pliny's first known involvement in Bithynian affairs.

The two cases were the talk of the town and Trajan often must have heard the name of the senator who had spoken so brilliantly and written so elegantly. In 103, he made him augur. Long time ago, augurs had been seers who studied the omens, but in the first century, being appointed as augur was similar to a decoration in our age. It was a normal reward for distinguished public service. Next year, the emperor made Pliny curator of the bed and banks of the Tiber and sewers of Rome. This was a serious job, and it must have appealed to Pliny's practical nature.

The treatment of waste is a severe problem in any metropolis. We do not know much about Pliny's adventures in water management. Except for a letter (#8.17) on the flooding of the Tiber, there was nothing that he found suited for publication. This is a pity, because in these years, Trajan dug several canals and founded two new harbors at Ostia and Centumcellae.

In 106-107, Pliny was again involved in the affairs of Bithynia. This time, he defended Varenus Rufus. It was a sensational lawsuit, because in 103, this man had conducted the case of the Bithynians against Julius Bassus. Now, he found himself in the dock. Pliny was successful: the case was dropped. Again, he gained inside knowledge of the eastern province.

Except for Julius Bassus and Varenus Rufus, three other governors of Bithynia had been accused in the preceding years. It was obvious that there was something seriously wrong -a financial crisis, as we shall see in an instant- and the emperor decided to intervene. We don't have to ask who was the new governor of Bithynia. Pliny was the obvious candidate. He was a good speaker, had a gift for dealing with people, had a practical nature, understood public finances. And so, Pliny set sail for Greece and Bithynia.