Gladiator

Gladiator: professional (or slave) fighter who engaged in combat in a Roman amphitheater.

Gladiator – nearly everybody has heard this word before and thinks they know what a gladiator is. But very often people have gained their knowledge only from Hollywood movies or TV series. These shed a totally wrong light on the gladiators and their lives. Indeed, we have a very good knowledge about the gladiators from artefacts, e.g. gravestones with inscriptions about their victories, fan articles like oil lamps, literature, and from excavations of amphitheaters and gladiator schools.

Origin

For a long time it was assumed that gladiatorial games came from the Etruscans. Depictions from Etruria do not show fights man against man though. Instead, they show fights of animals against men or even executions by animals like the Phersu game. Here, the convict is covered by a bag and attacked by a vicious dog.

Executions of noxii (condemned criminals) were indeed part of a munus (show) after the reform of emperor Augustus, where they took part at noon time. The beast fights (i.e, beast against beast or against a professional beast fighter, venator) took place in the morning. The highlight was the gladiator fights in the afternoon, in which trained professionals fought against each other in duels. Only very rarely did they fought in mass fights, the so called gregatim.

The first recorded gladiatorial combat took place in 264 BC at the funeral of Decimus Junius Brutus Pera, where three pairs fought against each other. In Paestum in Southern Italy, painted sarcophagi of rich, noble Lucanians have been found, which show ritual fights of two combatants, of which some show wounds. These could be assumed as predecessors to gladiatorial combat, although these combatants seem to be noble warriors fighting for the honor of their deceased chieftain, whereas the bustuarii at the funeral of Decimus Junius Brutus Pera were prisoners of war. Proposedly, the fights of the Lucanians were only until the first wound, while the three pairs in Rome had to fight to the death.

In the years to come the number of pairs increased, and since the fights became very popular among the people of Rome, the nobility used them to raise their popularity especially when running for office. That is why the fights became more and more detached from the actual funeral. Julius Caesar hosted a gladiatorial show in honor of his father and aunt, who both had died five years earlier. At this time he was candidate for the office of aedile.

Augustus reformed the gladiatura, and from his time on it was either the emperor who was allowed to host a munus, or a magistrate in a provincial town who was requested to do so by law. It was also during Augustus’ reign that a senatorial decree stated that Roman citizens should not appear publicly in the arena under a certain age. It was also disgraceful for the senatorial and equestrian classes to do so, since fighting for money as a gladiator was considered as infamis (dishonorable). This meant you lost your rights as a citizen to vote, run for office, and serve in the legions. Poor citizens did not care for these rights, and therefore the gladiatura attracted auctorati (volunteers) from the lower classes.

Gladiator Types

Augustus also reformed the types of gladiators. The first known gladiator types were derived from conquered peoples like the gallus resembling a Gaul and the samnis a Samnite from Southern Italy. Unfortunately, not much is known about these, since we do not have depictions which clearly identify them.

Better known is the murmillo, whose armatura was also derived from South-Italian peoples and who could be a successor to the samnis. The murmillo was equipped with a large scutum (big rectangular shield) similar to that of Roman legionaries. Because of the size of his shield, only a small greave on the left leg was necessary. He fought with a short sword or gladius. Most impressive was his helmet with a high angled crest. Some scholars assume that his name comes from a type of fish, but applied depictions of fish have never been found on helmets of murmillones.

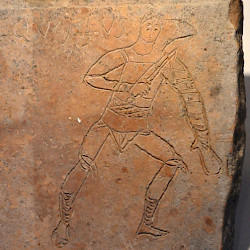

Sirmium, Tile with a retiarius |

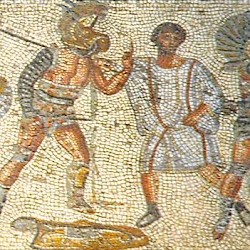

Ephesus, Theater decoration, Murmillo |

Ephesus, Theater decoration, Hoplomachus |

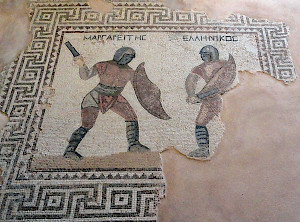

Thyatira, Relief of a gladiator (thraex) |

The armatura of the thraex was derived from the Thracians, a people coming from what is now Bulgaria. Their panoply was modified for fighting in the arena, e.g. the curved sica (a dagger-like sword) became angled. The thraex had a small rectangular shield and two high greaves to give him proper protection. The crest of his helmet was decorated with a griffin, a mythological animal associated with Thrace.

Another one of the older types of gladiators is the provocator. He was equipped with scutum and a gladius. He is the only gladiator type who wears breast protection. With this equipment he resembles a Roman legionary. The hoplomachus looked like a version of the Greek hoplite fighting with round shield and hasta (spear). Like the thraex he also had two high greaves.

In the mid-first century CE, the strangest gladiator appeared, and soon became highly popular: the retiarius. He was the only gladiator fighting without a helmet and was equipped with net, trident, and pugio. His only armor was a shoulder guard, the galerus. He was paired against the murmillo, but it was soon discovered that the net got entangled easily in the crest of the murmillo’s helmet. So a new shape of helmet was developed. This specialized murmillo was named secutor. The net was not just a gimmick. Properly thrown it could make it hard for the secutor to move his shield and wield his sword.

Equites were gladiators, who opened the munus in the afternoon by beginning the fight on horseback. After a while they dismounted to continue the combat on foot. They were equipped with a leather parmula (small round shield).

Another gladiator was the essedarius, who may have entered the arena in a chariot because his name is derived from essedus (chariot). However, there is no existing depiction of a gladiator on a chariot. There is also a debate among scholars how he was equipped.

There were even more unusual gladiator types, e.g. the dimachaerus meaning “two-sword-man”. An inscription in Pompeii announced a fight between dimachaerus and hoplomachus. Reliefs dating to the third and fourth centuries found in Asia Minor (nowadays Turkey) show a fighter holding two swords, but because one of them is behind his head, it is not clear whether he holds a sica (like the one in the other hand) or a straight gladius.

Female Gladiators

There is evidence that women fought as gladiators. The famous relief of Amazon and Achillia from Halicarnassus (today’s Bodrum in Turkey) is now on display at the British Museum in London. It shows two female fighters in the kit of provocatores.

Roman writer Petronius mentions an essedaria and there is literary evidence of venatrices (animal fighters) as well as legal texts forbidding high class women of a certain age to fight in the arena. Therefore we can assume that women could have fought in all classes of gladiators and that their combats were as serious as the men’s.

Daily Life of a Gladiator

Before a gladiator could appear publicly in the arena he had to get proper training. Although the majority of them were slaves or prisoners of war they were well cared for: they were fed, had a roof above their head, and even received medical treatment. These circumstances might also have attracted volunteers, because many poor citizens could not be sure about the next meal or accommodation, not to mention medical treatment.

The ludus (gladiator school) was run by a lanista (gladiatorial manager). He most probably hired former gladiators as trainers, called magistri or doctores. The gladiators received specialized training in their classes, but also general training like weight lifting.

The most basic training was against the palus. This was a post two meters high, against which the trainee had to thrust his sword and shield. This exercise built up a gladiator's stamina, but also taught the newbie to get a feeling for the correct measure.

The gladiators received three meals per day: as main course puls (a type of mash) made out of barley. This gave them the nickname hordearii (barley eaters). Four pegs found on some of the walls of the cells of the ludus in Pompeii led to the conclusion that four men must have been housed in one cell instead of two. They would have easily fit into one cell because bunk beds were already known to the Romans. After harsh training days, the gladiators could enjoy a hot steam bath and a massage.

The lanista rented out his gladiators to an editor of a munus (organizer of games) since the maintenance of a ludus was costly. The more often a gladiator fought and the more popular he got, the more money the lanista could get as rent for him. The lanista demanded a reimbursement for every dead gladiator as compensation for the costs for training and accommodation.

Ancyra, Tombstone of a gladiator |

Rabat, Figurine of a gladiator |

Gladiator helmet |

Oil lamp with a gladiator |

The Venue

The first gladiator fights of the so-called bustuarii took place next to the funeral pyre, which was called bustum. Soon after, the presentation of the combats was detached from the actual funeral, and hence took place at some more prominent places, e.g. the Forum Boarium (cattle market) in Rome or later at the Forum Romanum itself.

The fights became more and more popular, and candidates running for office used them to boast their popularity. Temporary wooden stands were erected to house the growing number of specatators. The first stone amphitheater was erected in 30 BC by T. Statilius Taurus on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars). Unfortunately, no traces of it remain, so it can only be assumed what it might have looked like. Suetonius mentions this amphitheater as part of Augustus’ building program. It burned down in the great fire of 64 CE.

The emperor Vespasian (r.69-79) started building the Flavian Amphitheater on a place where his predecessor, Nero (r.54-68) had had an artificial lake. By changing a lake into an amphitheater, Vespasian wanted to give back something to the people of Rome. This building became the archetype of all amphitheaters in the Roman world and is much better known under its nickname: the Colosseum. It received this nickname in Medieval times after a colossal statue of the Sun God, which used to stand in front of the amphitheater. A recent study by German archeologists suggests that the Colosseum might have been the renewal of an older building. The lake was supposedly much larger than the building area of the Colosseum, but it was still close by.

Anyhow, the Colosseum was the largest amphitheater, and many buildings all over the Roman Empire tried to imitate the grandeur of this venue. Since then, freestanding amphitheaters became the state of the art, e.g. the second amphitheaters of Puteoli (Pozzuoli) and Capua (Sta. Maria Capua Vetere). There were earlier examples of freestanding amphitheaters, e.g. the one in Verona, but most of the earlier stone amphitheaters were built partially into hill slopes. The earliest example of a stone-built amphitheater is the one in Pompeii, which is also part of the city wall.

Thysdrus, Amphitheater, Arena |

Augusta Emerita, Amphitheater, arena |

Lepcis, Amphitheater |

Pompeii, Amphitheater |

The amphitheater was a genuine Roman invention. The Greeks only knew theaters for scenic displays, stadia for sports events, and hippodromes for any equestrian competitions. The elliptical shaped arena in an amphitheater ensured view from every seat, while the staircases made it easy to find your seat, yet keeping the various orders (Senatorial, equestrian...) separated. The senators with the front row seats did not need to mingle with the low class and slaves of the upper tiers. The emperor, of course, had his own box, where he and his family could watch the shows.

In the Eastern part of the Roman Empire only a few amphitheaters were built, although gladiator games were popular there as well. Instead, by building walls to separate the seating area from the arena, stadions and theaters were adjusted to house venationes and gladiator fights.

The End of Gladiator Games

The gladiator games did not come to an end suddenly. On the contrary, there was a slow decline, which ended in the West earlier than in the East. The deepest cause of the demise was not Christian opposition to the games, but the declining Roman economy. For instance, a decree of CE 325 by the emperor Constantine declared that all criminals should be sent to the mines and not ad ludos, because he needed mine workers. That Contantine did not oppose gladiatorial games in general is shown by his response in 337 CE to the request of the Umbrian town Hispellum, in which he granted the inhabitants permission to hold munera, so that they did not have to go to the rival city of Volsinii.

Further, the old symbolism of granting outcasts a return into society was not needed anymore in Late Roman society, which was mainly Christian. Outcasts now had a chance to return into community by receiving the sacraments of baptism and repentance. Gladiator games were still popular at the end of the fourth century when the monk Telemachus traveled from the eastern part of the Empire to Rome, where he attended a gladiatorial show at the amphitheater. He wanted to stop the fights, so he stepped down into the arena. This enraged the audience and they stoned him to death. Consequently, the emperor Honorius banned gladiatorial games, not because he was against them, but as a punishment for the stoning. This was similar to what Nero did after the hooligan fights in 59 CE, which took place in Pompeii.

Reports mention that the last gladiatorial combats in the Colosseum took place in 434 or 435, whereas venationes continued until 523, when a Roman consul hosted them, while the Ostrogoths under Theoderic were already reigning in Rome and Italy.