Pliny the Younger

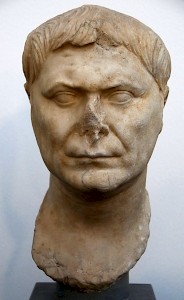

Pliny the Younger or Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (62-c.115): Roman senator, nephew of Pliny the Elder, governor of Bithynia-Pontus (109-111), author of a famous collection of letters.

The Roman senator Pliny the Younger is one of the few people from Antiquity who is more to us than just a name. We possess a long inscription which mentions his entire career, one or two of his houses have been discovered, and -more importantly- we can still read many of his letters. They are often very entertaining: he tells a ghost story, gives accounts of lawsuits, guides us through his houses, describes the friendship of a boy and a dolphin, informs us about the persecution of Christians, tells about the eruption of the Vesuvius. But we can also read his correspondence with the emperor Trajan. With the senator Cicero and the father of the church Augustine, Pliny is the best-known of all Romans.

In this article, we will first describe his career, and then focus on his governorship of Bithynia-Pontus (109-111), where he was some sort of interim-manager who had to settle a troubled province. His opinions and world view will be discussed passingly - you can better read his letters.

Youth

In 62, a rich Roman knight named Lucius Caecilius and his wife Plinia of Como (Novum Comum) in northern Italy became parents of a son, Gaius Caecilius Secundus. Unfortunately, the father soon died, and the young man was (later) adopted by Plinia's brother, Gaius Plinius Secundus. The boy took over his uncle's name and became known as Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus. In English, nephew and uncle are usually called Pliny the Younger and Pliny the Elder.

The younger Pliny was brought up in the houses of his uncle, in Como and Rome. Pliny the Elder had been a cavalry officer in the Rhine army and had some literary pretensions. He had published two books on military matters and had written one of the first Latin biographies. When he had returned to Italy, three years before his nephew's birth, he had found his further career obstructed. We do not know why, but it is easy to believe that there was no room for a military man at the court of the emperor Nero, who preferred the company of musicians, singers, dancers, and other performers. Pliny the Elder had started a career as a scholar, and was preparing a book on Problems in grammar. It was a safe occupation.

During the younger Pliny's youth, the political situation was deteriorating. Nero was becoming more and more of a tyrant, until in the spring of 68, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, Gaius Julius Vindex, revolted. Many senators were sympathetic to this revolt, but the general of the army of the middle Rhine, Lucius Verginius Rufus (a friend of Pliny the Elder), suppressed the rebellion. However, the Senate declared that Nero was an enemy of the state and proclaimed Servius Sulpicius Galba, an ally of Vindex, emperor. Nero committed suicide.

This was the beginning of a terrible civil war. Galba despised the soldiers of the Rhine army, who first offered the throne to Verginius Rufus (who refused) and then to the general of the army of the lower Rhine, Aulus Vitellius (January 69). Galba panicked, made mistakes, and was lynched by soldiers of the imperial guard, which placed a rich senator named Marcus Salvius Otho on the throne, but he was defeated by the army of Vitellius. He had only just reached Rome, when the news arrived that in the east, where the Romans were fighting a war against the Jews, another general had revolted: Vespasian. The armies of the Danube immediately sided with the new pretender and defeated Vitellius' army (December 69). The reign of Vespasian could begin.

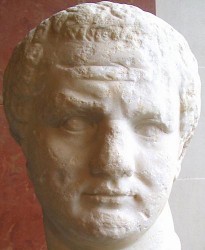

To the Plinii, this was an important change - for the better. The old officer was a close friend of one of the sons of the emperor, Titus: both men had been together in Germania. In 70, Pliny the Elder was made procurator and sent to Gallia Narbonensis, Africa, Hispania Terraconensis, and Gallia Belgica. He did not return until 76, when he became one of the emperor's personal advisers and (perhaps) prefect of the Roman fire brigade.

During his absence, the elder Pliny was no longer able to take care of his nephew, who was eightyears old when his uncle resumed his career. A guardian was appointed: Verginius Rufus, the man who had refused the imperial purple. He had been rewarded, but in fact, his career was at a dead end, and he founded a literary salon. Many important authors visited him, and among them was the famous orator Nicetes of Smyrna, who became the younger Pliny's teacher in Greek and rhetoric. His Latin teacher was Quintilian, professor in Latin rhetoric and one of the most influential authors of his age.

Pliny had to study rhetoric, because was essential to be able to speak in public. Since a speech is only convincing when the speaker looks reliable, there was a lot more to rhetoric than only speaking: it was a complete program of good manners and general knowledge.

It was impossible to find better teachers. Pliny's style of writing is, therefore, more polished than that of his uncle. His first literary work was a tragedy, which he wrote 75 or 76. We do not know what it was about, except that it was in Greek. It was the beginning of a long love for the theater. Two of his villa's at Lake Como were called Comedy and Tragedy.

When Pliny was seventeen years old, his uncle died (25 August 79). His last office was that of admiral of one of Rome's navies, which was stationed at Misenum near Naples. When the Vesuvius erupted, the elder Pliny wanted to rescue people and do some scientific research, but he did not survive. His nephew, who was now adopted, inherited his uncle's possessions. He had already inherited the country houses and money of his father, and must have been a rich man. And rich men were, in Antiquity, supposed to take their responsibility. He had to embark upon a public career.