Hittites

Q5406Hittites: ancient nation in Central Anatolia, named after their capital Hattusa, builders of one of the great Bronze Age empires.

Origin

When scholars started to study the archives of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites, they were surprised to discover texts in no less than eight languages. This tells a lot about the background of the Hittite Empire.

One of the oldest languages must have been Hattic, which can be traced back to the third millennium BCE. The inhabitants of Alacahöyük must have spoken this language. Towards the end of the third millennium, Indo-European tribes started to arrive from Anatolia, who brought four new languages: Palaic (associated with the cult of the weather god Zaparwa), two Luwian languages (spoken in the western part of Anatolia), and a language that was called "Nešili" by its speakers.

The speakers of this last-mentioned language would settle in central Anatolia, within the great arc of the river Halys, and would start to use an older city, Hattusa, as their capital. Hence, they are now called "Hittites" and their language is called "Hittite" (although "Nešili" would have been more correct).

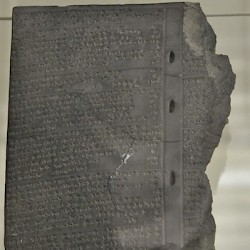

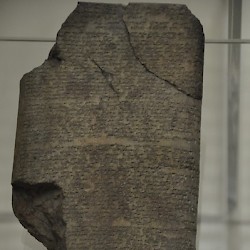

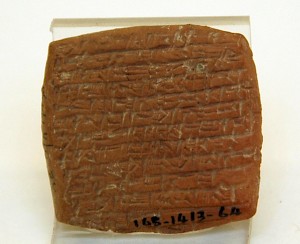

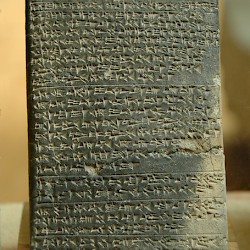

The disturbance created by the migration of these tribes is documented in the archive of cuneiform texts that was found in Kültepe (ancient Kaneš or Nesa). The texts, written by merchants from Assyria who had founded a karum (a trading outpost) at walking distance from the royal palaces of Kaneš, document an Anatolian society with several city-states, including Kaneš, a still unidentified town called Kussara, and Hattusa. The tablets refer to the immigrants and presuppose a lengthy process of both gradual infiltration and open warfare. By the mid-eighteenth century BCE, a king Anitta of Kussara had unified several city-states and had started to call himself "great king". His palace has been identified in Kaneš.

Kaneš was destroyed in the mid-eighteenth century by an unknown enemy, after which we have no written information. This lacuna in our understanding lasts for about a century. When we have written sources again, by the mid-seventeenth century BCE, we read about a king who claims to descend from the rulers of Kussara but has taken up residence in Hattusa, and has named himself after his city: Hattusili I.

Old Kingdom

The first kings of the Hittite Kingdom were surprisingly successful. Their conquests are documented in the historical introduction to the "edict" of a later king, Telepinu. He mentions a king Labarna as the kingdom's founder and tells how Labarna's successor Hattusili (r. c.1650-c.1620)note fought several wars, making their "kingdom neighbor to the sea", and even adding Kizzuwatna (Cilicia), the fertile plain south of the Taurus Mountains. This southward expansion brought the Hittites in conflict with the kingdom of Halpa or Halab in northern Syria (modern Aleppo).

Although certain towns were captured and permanently garrisoned, these wars were usually plundering campaigns. In the first years of the sixteenth century - in 1587 BCE, according to the low middle chronology, Mursili I even reached and sacked Babylon. This had no real consequences for the Hittites, but created chaos in Mesopotamia, where the ruling dynasty was replaced and local powers were important.

One of these was Mitanni, which became a major competitor of the Hittites. Partly as a consequence of the rise of this rival power, the Hittites were unable to consolidate their gains. During the reign of Hantili I (r.c.1585-c.1560), a crisis in the ruling dynasty led to the collapse of Hittite power. The next kings (Zidanta, Ammuna, and Huzziya) were quite ineffective, until Telepinu (r.c.1525-c.1500) restored order and laid down the principles of decent government in the decree mentioned above. It was a sign of the times that the relation with Kizzuwatna was defined in a treaty: the country was no longer subject, but independent.

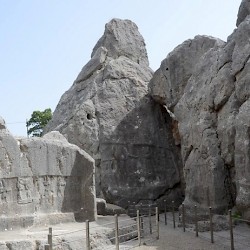

Alacahöyük, Sphinx Gate |

Alacahöyük, Hittite Palace |

Alacahöyük, Sphinx Gate, Relief (copy) |

Alacahöyük, Hittite vase (Old Kingdom) |

New Kingdom

Telepinu is usually associated with a Middle Kingdom, but essentially, we know very little about the fifteenth century, apart from the fact that the Hittite state was threatened from all sides. Telepinu's eighth successor was named Tudhaliya I, ruled from c.1420 to c.1400 and was the ruler from a new dynasty. He was succeeded by Arnuwanda and two other Tudhaliyas, until in c.1355 BCE, Šuppililiuma became king.

He was the founder of the New Kingdom and the creator of a professional army of hundreds of chariots. During a reign of thirty-five years, he defeated Mitanni in the southeast and invaded Syria, which had for more than a century been held by the Egyptians. Benefiting from Egypt's domestic problems during the reign of Akhenaten, Šuppililiuma added the northern part of Syria to the Hittite Kingdom. In about 1320, he left his kingdom to his eldest son Arnuwanda II, and appointed younger sons as vice-kings in Aleppo and Karchemish.

An interesting incident is the "dahamunzu episode": the widow an Egyptian king requesting a Hittite prince as her new consort. Unfortunately, we do not know whether this woman had been the wife of Akhenaten (who died in 1336) or Tutankhamun (died in 1327), but it is obvious that the Hittites were now considered a serious power. It also proves that the Egyptian court did not really care about the loss of its northern territories.

After the brief reign of Arnuwanda II, another son of Šuppililiuma became king: Mursili II (r. c.1318-c.1290). At the beginning of his reign, he managed to overcome Arzawa, a powerful federation in western Anatolia. It was divided into three vassal kingdoms: Seha (the valleys of the Caicus and Hermus), Haballa (the interior), and Mira (the valley of the Meander). At this moment, the Hittite Empire consisted of central and southern Turkey with northern Syria, while western, northern, and eastern Turkey were part of the Hittite zone of influence.

Western Affairs

Mursili's son Muwatalli II (r.c.1290-c.1272) had to cope with some problems in the west, where an adventurer named Piyamaradu created a lot of trouble. He received support from one Tawagawala of Millawanda, the brother of the king of Ahhiyawa. All names are Greek: Tawagawala is *Etewokleweios or Eteocles, Millawanda is the city of Miletus, and Ahhiyawa is a rendering of Achai(w)a and probably refers to a state in Mycenaean Greece.

The rebel attacked Wilusa (also known as Troy), forcing its king Alaksandu to ask for help from the Hittites. (The name Alaksandu resembles the Alexandros of the Iliad.) King Muwatalli first ordered the king of Seha to support Wilusa, but when he was defeated by Piyamaradu, he personally intervened. After this, Wilusa was a vassal of the Hittites. The treaty survives in no less than six copies; the terms were guaranteed by a Trojan god named Apalliunas, who is better known as Apollo.

It is certain that the support that the Ahhiyawans offered to the rebel Piyamaradu was military in nature, because a later Hittite ruler, Hattusili III (r.c.1265-c.1240) refers, in a document known as the "Tawagawala letter", to an armed conflict between himself and the king of Ahhiyawa - a conflict that had in the meantime been settled peacefully, which gives Hattusili confidence to call upon his "brother" to help him finally solve the Piyamaradu affair.

It is possible that the (indirect) military support of the king of Ahhiyawa to Piyamaradu is the historical nucleus of the stories about the Trojan War, but we can be sure only when we will have a tablet that mentions an Ahhiyawan king actually attacking Wilusa.

Southern Affairs

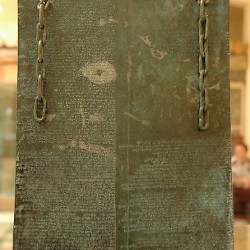

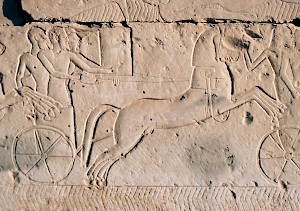

While the Hittites were dealing with Piyamaradu in the west, a new dynasty had come to power in Egypt: the Nineteenth Dynasty. One of its kings, Ramesses II, decided to reconquer northern Syria. This forced king Muwatalli to concentrate his forces in the south, where he managed to catch the Egyptian by surprise on the plain of the river Orontes, where a great battle between two chariot armies took place in 1274. Both sides claimed victory and there were new campaigns, but in 1259, a treaty was concluded, in which Syria was divided between the two superpowers.

The Egyptian account of the battle (an inscription on a wal in Luxor) mentions several allies of the Hittites: Mitanni (which must refer to the southwestern provinces, ruled by the vice-king in Karchemish), Kizzuwatna (the vice-kingdom in the south), Arzawa (the former federation in the west), and the Dardany, who may have lived in the area of Troy. The only parts of Anatolia that were outside Hittite control were Masa in the northwest, Greek Millawanda in the west, and Lukka in the southwest.

The Orontes and Tell Kadesh |

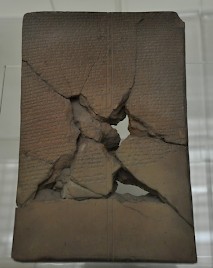

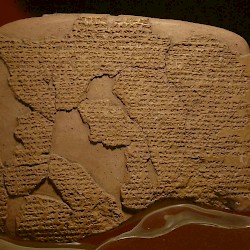

Hattusa, Kadesh Treaty |

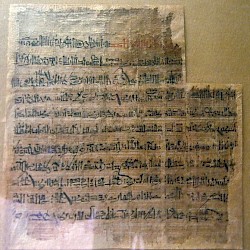

An Egyptian poem about the battle of Kadesh |

Hattusa, Letter from the Hittite queen Puduhepa to the Egyptian queen Nefertari |

The End

In spite of the Hittite successes, there were troubles as well. In the east, the Assyrian kingdom was benefiting from the demise of Mitanni, and it has been argued that the Hittites were willing to conclude a peace treaty with Egypt to have a free hand to deal with Assyria. We also learn about northern enemies, the Kashka, who could be quite aggressive.

The foreign enemies were not the only problems the successors of Muwatalli II had to deal with. There were problems within the royal house as well. His first son, Mursili III (r.c.1272-c.1265) had to send a relative into exile and was dethroned by Hattusili III, who was forced to create a new vice-kingdom, Tarhuntassa, in the southwest. We already noticed that he had to request support from the king of Ahhiyawa to solve the Piyamaradu affair.

Hattusili's son Tudhaliya IV (r.c.1240-c.1215) was still residing in Hattusa and ordered the reliefs at nearby Yazılıkaya, but the problems were increasing. Hattusa was evacuated - it was dangerously exposed to Kashka attacks - and during the reigns of Arnuwanda II and Šuppililiuma II, we read about a civil war with the vice-king of Tarhuntassa. What really happened, is unclear: precisely because the empire collapsed, we have only a couple of written sources.

Still, it seems reasonably clear that after c.1190 BCE, power was in the hands of the vice-kings of Tarhuntassa and Karchemish. These two states would split up in several minor kingdoms (the Neo-Hittite successor states). The demise of the Hittite state also created a power vacuum, which was filled by invaders from the Balkans (the Phrygians). Several nations, usually called the "Sea People", would start to wander and created great unrest in the eastern Mediterranean. The Assyrian Empire would in the end recreate some stability.

Yazılıkaya, Chamber A, general view |

Yazılıkaya, Chamber A, Central Relief |

Yazılıkaya, Chamber B, Tudhaliya IV |

Yazılıkaya, Chamber B, Gods of the Underworld |