Titus' Siege of Jerusalem

Roman-Jewish Wars: name of several military engagements between the Roman Republic (later: Empire) and various groups of Jews between 63 BCE and 136 CE.

Titus' Siege of Jerusalem

His father's accession to the Roman throne left the war against the Jews to Titus. He was not a very experienced general, but his assistant was Tiberius Julius Alexander, who had been governor of Judaea in 46-48 and knew how to fight a war. Titus' own quality was that the new emperor, his father, could trust him.

His father's strategy, to allow the Jews in Jerusalem to destroy themselves, had been successful. Besides the Zealots of Eleazar son of Simon and the private army of John of Gischala, a new leader had come to power, Simon bar Giora ("son of the proselyte"?). He was supported by men from Idumea, the southern part of Judaea that the Romans had reconquered only recently. John and Simon had different agendas. The first strove only for political freedom and minted silver coins with the legend "Freedom of Zion". Simon, on the other hand, stood at the head of a messianic movement; his copper coins have the legend "Redemption of Zion".

On 14 April 70, during Passover, Titus laid siege to Jerusalem. To the northeast of the old city, on Mount Scopus, the legions XII Fulminata (a new addition from Syria) and XV Apollinaris shared a large camp; V Macedonica was camped at a short distance. When X Fretensis arrived from Syria, it occupied the Mount of Olives, in front of the Temple. The soldiers of this legion had a special incentive to fight: they had been defeated by the Zealots in 66, and wanted revenge.

Auxiliaries had been sent by two petty kingdoms on the Upper Euphrates, Commagene and Emesa; an Arab sheik, who felt a deep hatred for the Jews, had joined the Romans with his warriors; and from Italy arrived many adventurers - veterans from the defeated armies of Galba and Otho. The besieged did not stand a chance against this army.

During this same Passover, Eleazar allowed all inhabitants to perform their religious duties in the Temple. The festival, however, was spoilt by John's men, who took swords with them and forced Eleazar's Zealots into surrender.

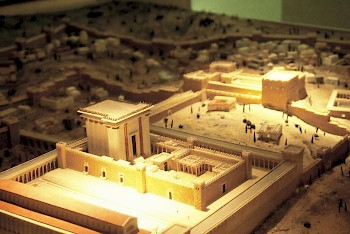

The city as a whole consisted of four parts.

- The Old Town was situated on a steep plateau in the south; its walls, which faced the Valley of Hinnom in the west and south, were old but almost impossible to assail. Here, Simon was in charge; he commanded 10,000 Jewish warriors and 5,000 Idumeans.

- In the east was the Temple complex, occupied by Eleazar's Zealots, 2,400 in number, but since the Passover massacre, they were controled by John. This inner bulwark was next to the Kidron ravine, which prevented any attack. Part of the Temple complex was a lofty castle called Antonia.

- West of the Temple complex was the New Town, which had walls of its own, built in the forties. It was occupied by the 6,000 men of John's militia.

- More to the north was a quarter named Bezetha (which also means New Town). Bezetha had only recently been added to the city; it had not many inhabitants and old graves could still be seen between the houses. Since the siege started at Passover, half a million pilgrims were trapped inside the city, and were forced to live in tents in Bezetha. Its walls were high and a series of sixty feet high towers dominated the scene, but for the Romans there was at least one advantage: there was no valley in front of them. It was the logical place to attack Jerusalem.

After this success, John wanted to launch a preemptive strike at the Romans, who were building new camps to the west of the city: one for the legions XII Fulminata and XV Apollinaris and one for legion V Macedonica. But John was afraid that Simon would close the city gates behind his back, and did not assail the new camps. As a consequence, the legions were able to build their redoubts almost without any trouble; soon, their catapults started to throw heavy stones into the city. Under cover of this artillery fire, the Roman soldiers could start to bash the northern wall with their battering-rams.

The Roman attack served to unite the Jews, who started to make sorties, but failed to destroy the new weapon that the Romans had prepared: siege towers. These were taller than the walls and enabled the legionaries to throw missiles on the defenders of the walls; when the latter tried to evade the missiles, the battering-rams could do their work. After fifteen days, the wall collapsed, and the Jews withdrew from Bezetha to their second wall. Titus ordered an all-out attack on this wall, where the defences were still unorganized. The men of John and Simon were able to ward off the danger for four days, but on the fifth day the second wall yielded to the violence of the battering-rams.

Fighting continued in the streets of the New Town, where the defenders inflicted heavy losses upon the Romans, who were forced to retire through the breach to Bezetha. After four days of heavy fighting, the latter again managed to drive away the Jews from the second wall, which was immediately destroyed.

Titus now decided upon a show of strength, and staged an army parade, which lasted for four days. Meanwhile, his adviser Flavius Josephus was to talk to the men on the walls, trying to induce them to surrender. The Jewish leaders were not impressed by the arguments of the turncoat, and on the fifth day, the Roman soldiers renewed the struggle: they started to build four large siege dams, aimed at the Antonia fortress. (It was to be taken by force, because it had large stores an two great cisterns.) The Roman attack was no success: John's sappers undermined one of the dams and managed to raise a fire on a second one, and Simon's soldiers destroyed the remaining dams two days later.

The Roman commanders now knew that their enemies would fight for every inch of their city, and understood that the siege of Jerusalem would take a long time. Therefore, Titus changed his plans.There were signs that the supplies of Jerusalem were giving out: some Jews had left the city, hoping to find food in the valleys in front of the walls. Many of them had been caught and crucified - some five hundred every day. (The soldiers had amused themselves by nailing their victims in different postures.) The Romans decided to starve the enemies into surrender. In three days, Jerusalem was surrounded with an eight kilometer long palisade. All trees within fifteen kilometres of the city were cut down. The camps of the legions V Macedonica, XII Fulminata and XV Apollinaris were demolished; these troops were billeted on Bezetha.

The death rate among the besieged increased. Soon, the Kidron valley and the Valley of Hinnom were filled with corpses. One defector told Titus that their number was estimated at 115,880. Desperate people tried to leave Jerusalem. When they had succeeded in passing their own lines and had not been killed by Roman patrols, they reached the palisade. Here they surrendered: as prisoners, they were at last entitled to some bread. Some of them ate so much, that they could not stomach it and died. In that case, their oedemaous bodies were cut open by the Syrian and Arab warders, who knew that some of these people had swallowed coins before they started their ill fated expedition. Titus refrained from punishing these violators when he discovered that there were too many. One of the defectors was the famous teacher Yohanan ben Zakkai, who escaped in a coffin and saved his life by predicting Titus that he, too, would be an emperor.

Since there was no wood, the construction of new siege dams to attack the Antonia took three weeks. A sortie of weakened Jewish warriors had no success. Soon, the sound of the battering-rams was to be heard, and one night, a wall of the Antonia collapsed; but the legionaries discovered that a new wall had been build behind the breach. The Antonia had to be taken by other means.

During a dark night at the beginning of July, twenty-four Roman soldiers climbed the walls of the castle, killed the guard, and sounded a trumpet. The garrison of the Antonia overestimated the number of enemies; many fled to the Temple. At the same time, Titus ordered his men to enter the mine that John's sappers had made. At three o' clock in the morning, these men entered the fortress; after ten hours of fighting, they had driven John's men away.

A couple of days later, on 14 July, prisoners told them that the priests in the Temple had been forced to interrupt the daily sacrifices, which had greatly demoralized the defenders of Jerusalem.

The Antonia was demolished. The stones were used to build a new dam, this time towards the Temple terrace. The Romans used the dam to set fire to the porticoes on the northern and western side of the terrace, but it was impossible to bash trough the walls. On the tenth of August, the Temple itself was burning. Six thousand women and children were taken prisoner at the Court of the Gentiles, while the legionaries sacrificed to their standards in the Holy of Holies.

The Temple was intentionally set in fire. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus writes in his Jewish War 6.220-270 that the Roman soldiers took the initiative, but this is not true. A fourth-century writer, Sulpicius Severus, states that Titus ordered the destruction of the sanctuary, and this piece of information almost certainly stems from the Roman historian Tacitus.note It is more probable that Flavius Josephus invented his story to absolve his friend Titus from the responsibility of this war crime, than that Tacitus was slandering.

During the next few days, the Romans destroyed the archives, the quarter immediately south of the Temple, and the building where the Sanhedrin convened. Then, they descended into the Old Town. Meanwhile, dams had been prepared to attack the palace; when Titus' men had taken it, the last defenders managed to hide themselves in the sewer system. John was among them, and was among the first to surrender. Simon remained in hiding for some time, but finally made a dramatic appearance on the place where the Temple had stood, dressed in a white priestly tunic and his royal, purple mantle. On 8 September, Titus was master of what was left of the city.

There seems to have been some talk of the succesful general revolting against his father. Some 160 years later, the Greek author Philostratus published a biography of a contemporary of Titus, the charismatic teacher Apollonius of Tyana, and he has Apollonius praise Titus for his obedience.

On his return in Rome, Vespasian, Titus and their soldiers celebrated a triumph. They paraded through the streets of their capital in a beautiful procession, which culminated in the punishment of the Jewish leaders: Simon son of Giora was executed and John of Gischala was sentenced to life imprisonment. The sacred vessels, the table on which the Bread of God's Presence had been put, the Menorah, the curtain and all the other objects that nobody except the high priest was allowed to see, were carried through the Roman streets.

The boundless riches from the Temple treasury were used to strike coins with the legend JUDAEA CAPTA ("Judaea defeated"). Any Roman would be reminded of their emperor's victory. The Jews were forced to pay an additional tax (fiscus Judaicus).

During the four years of war, the Romans had taken 97,000 prisoners. Thousands of them were forced to become gladiators and were killed in the arena, fighting wild animals or fellow gladiators. Some, who were known as criminals, were burned alive. Others were employed at Seleucia, where they had to dig a tunnel. But most of these prisoners were brought to Rome, where they were forced to build the Forum of Peace (a park in the heart of Rome) and the Colosseum. The Menorah and the Table were exhibited in the temple of Peace.

In front of one of Rome's Jewish quarters a triumphal arch was erected to honor Titus. Another arch was built on the Forum Romanum, where it can still be seen. The first arch was destroyed in the Middle Ages; its inscription, however, was copied by an anonymous monk from Einsiedeln (Switzerland) who visited Rome in the eighth century.

Senate and People of Rome to thir princeps, Imperator Titus Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian, high priest, in the tenth year of his tribunal powers, seventeen times Imperator, eight times consul, father of the fatherland, because he (on his father's orders and auspices and using his advice) subdued the Jewish people and destroyed the city of Jerusalem, something which none of the leaders, kings and armies before him failed to do.