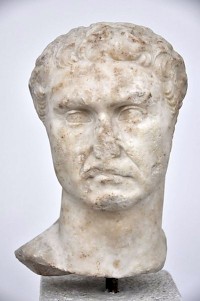

Herod the Great

Herod (73-5/4 BCE) was the pro-Roman king of the small Jewish state in the last decades before the common era.

Early years

Herod was born 73 BCE as the son of a man from Idumea named Antipater and a woman named Cyprus, the daughter of an Arab sheik. Antipater was an adherent of Hyrcanus, one of two princes who struggling to become king of Judaea.

In this conflict, the Roman general Pompey intervened in Hyrcanus' favor. Having favored the winning side in the conflict, Antipater's star rose, especially since he cooperated with the Romans as much as possible. In the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar, Hyrcanus and Antipater sided with the latter, for which especially the courtier was rewarded: in 47, he was appointed epitropos ("regent") and received the Roman citizenship.

It was obvious that Antipater was the real power behind Hyrcanus' throne. He managed to secure the appointment of his son Herod to the important task of governor of Galilee. He launched a small crusade against bandits, which made him very popular with the populace and impopular with the Sanhedrin.

On March 15, 44 BCE, Caesar was murdered. The new leaders in Rome were Caesar's nephew Octavian and Caesar's powerful second-in-command Mark Antony. They announced that they would punish Caesar's murderers, Brutus and Cassius, who fled to the East. Cassius ordered all provinces and principalities to pay money for their struggle against Octavian and Mark Antony, and Judaea had to pay some 15,000 kg of silver. Antipater and his sons had to take harsh measures to get the money, and in the ensuing troubles, Antipater was killed. With Roman help, Herod killed his father's murderer.

In 43, Hyrcanus' nephew Antigonus tried to obtain the throne. Herod defeated him, and secured the continuity of the line of Hyrcanus by marrying his daughter Mariamme. Of course, the young man was not blind to the fact that this marriage greatly enhanced his own claim to the throne.

Meanwhile, Octavian and Mark Antony had defeated Brutus and Cassius (at Philippi, in 42). Herod managed to convince Mark Antony, who made a tour through the eastern provinces that had supported Caesar's murderers, that his father had been forced to support their side. The Roman leader was convinced, and awarded Herod with the title of tetrarch of Galilee, a title that was commonly used for the leaders of parts of vassal kingdoms. (Herod's brother Phasael was to be tetrarch of Jerusalem; Hyrcanus remained the Jewish national leader in name only.)

This appointment caused a lot of resentment among the Jews. After all, Herod was not a Jew. He was the son of a man from Idumea; and although Antipater had been a pious man who had worshipped the Jewish God sincerely, the Jews had always looked down upon the Idumeans as racially impure. Worse, Herod had an Arab mother, and it was commonly held that one could only be a Jew when one was born from a Jewish mother. When war broke out between the Romans and the Parthians (in Iran and Mesopotamia), the Jewish populace joined the latter. In 40, Hyrcanus was taken prisoner and brought to the Parthian capital Babylon; Antigonus became king in his place; Phasael committed suicide.

Herod managed to escape and went to Rome, where he persuaded Octavian and the Senate to order Mark Antony to restore him. And so it happened. After Mark Antony and his lieutenants had driven away the Parthians, Herod was brought back to Jerusalem by two legions, VI Ferrata (whose men had already fought in Gaul and the civil wars) and another legion, perhaps III Gallica (37 BCE). Antigonus was defeated and after he had besieged and captured Jerusalem, and had defeated the last opposition (more), Herod could start his reign as sole ruler of Judaea. He assumed the title of basileus, the highest possible title.

Early reign

Herod's monarchy was based on foreign weapons; the start of his reign had been marked by bloodshed. His first aim was to establish his rule on a more solid base. Almost immediately, he sent envoys to the Parthian king to get Hyrcanus back from Babylon. The Parthian king was happy to let the old man go, because he was becoming dangerously popular among the Jews living in Babylonia. Although Hyrcanus was unfit to become high priest again, Herod kept his father-in-law in high esteem. The support of the old monarch gave an appearance of legality to his own rule.

The new king started an extensive building program: Jews could take pride in the new walls of Jerusalem and the citadel which guarded its Temple. (This fortress was called Antonia, in order to please Herod's patron Mark Antony.) Coins were minted in his own name and showed an incense burner on a tripod, intended to signify Herod's care for the orthodox Jewish cult practices. These coins had a Greek legend - HÈRÔDOU BASILEÔS - which indicates that Herod considered his standing abroad. And the new king continued to please the Romans, to make sure that they would continue their support. He sent lavish presents to their representative in the East, Mark Antony, and to his mistress, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

These gifts almost were Herod's undoing. The relations between on the one hand Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the East and on the other hand Octavian and the Senate in the West became strained, and civil war broke out in 31. It did not last very long: in August, the western leader defeated the eastern leader, who fled to Alexandria. For the first time in his life, Herod had aligned himself with a loser.

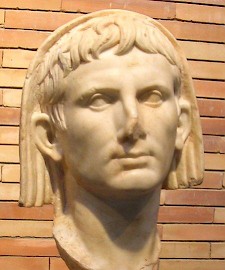

He managed to solve this problem, however. First, he had Hyrcanus executed, making sure that no one else could claim his throne. Then, he sailed to the island of Rhodes, where he met Octavian. In a brilliant speech, Herod boasted of his loyalty to Mark Antony, and promised the same to the new master of the Roman Empire. Octavian was impressed by the man's audacity, confirmed Herod's monarchy, and even added the coast of Judaea and Samaria to his realm. Actually, Octavian did not have much choice: his opponents were still alive, and if he were to pursue them to Egypt, Herod could be a useful ally. As it turned out, Mark Antony and Cleopatra preferred death to surrender, and Octavian became the only ruler in the Roman world. Under the name Augustus, he became the first emperor. He rewarded his ally with new possessions: a.o. Jericho and Gaza, which had been independent.

Later reign

Herod's position was still insecure. He continued his building policy to win the hearts of his subjects. (A severe earthquake in 31 BCE had destroyed many houses, killing thousands of people.) In Jerusalem, the king built a new market, an amphitheater, a theater, a new building where the Sanhedrin could convene, a new royal palace, and last but not least, in 20 BCE he started to rebuild the Temple. And there were other cities where he ordered new buildings to be placed: Jericho and Samaria are examples. New fortresses served the security of both the Jews and their king: Herodion, Machaerus, and Masada are among them.

But Herod's crowning achievement was a splendid new port, called Caesarea in honor of the emperor (the harbor was called Sebastos, the Greek translation of "Augustus"). This magnificent and opulent city, which was dedicated in 9 BCE, was built to rival Alexandria in the land trade to Arabia, from where spices, perfume and incense were imported. It was not an oriental town like Jerusalem; it was laid out on a Greek grid plan, with a market, an aqueduct, government offices, baths, villas, a circus, and pagan temples. (The most important of these was the temple where the emperor was worshipped; it commanded the port.) The port was a masterpiece of engineering: its piers were made from hydraulic concrete (which hardens underwater) and protected by unique wave-breaking structures.

Although Herod was a dependent client-king, he had a foreign policy of his own. He had already defeated the Arabs from Petra in 31, and repeated this in 9 BCE. The Romans did not like this independent behavior, but on the whole, they seem to have been very content with their king of Judaea. After all, he sent auxiliaries when they decided to send an army to the mysterious incense country (modern Yemen; 25 BCE). In 23, Iturea and the Golan heights were added to Herod's realms, and in 20 several other districts.

With building projects, the expansion of his territories, the establishment of a sound bureaucracy, and the development of economic resources, he did much for his country, at least on a material level. The standing of his country -foreign and at home- was certainly enhanced. However, many of his projects won him the bitter hatred of the orthodox Jews, who disliked Herod's Greek taste - a taste he showed not only in his building projects, but also in several transgressions of the Mosaic Law.

The orthodox were not to only ones who came to hate the new king. The Sadducees hated him because he had terminated the rule of the old royal house to which many of them were related; their own influence in the Sanhedrin was curtailed. The Pharisees despised any ruler who despised the Law. And probably all his subjects resented his excessive taxation. According to Flavius Josephus, there were two taxes in kind at annual rates equivalent to 10.7% and 8.6%, which is extremely high in any preindustrial society.note It comes as no surprise that Herod sometimes had to revert to violence, employing mercenaries and a secret police to enforce order.

On moments like that, it was clear to anyone that Herod was not a Jewish but a Roman king. He had become the ruler of the Jews with Roman help and he boasted to be philokaisar ("the emperor's friend"), entertaining Agrippa, Augustus' right-hand man. On top of the gate of the new Temple, a golden eagle was erected, a symbol of Roman power in the heart of the holy city resented by all pious believers. Worse, Augustus ordered and paid the priests of the Temple to sacrifice twice a day on behalf of himself, the Roman senate and people. The Jewish populace started to believe rumors that their pagan ruler had violated Jewish tombs, stealing golden objects from the tomb of David and Solomon.

Marriages

Herod concluded ten marriages, all for political purposes. They were probably all unhappy. His wives were:

- Doris, from an unknown family in Jerusalem: married c.47, sent away 37; recalled 14, sent away 7/6.

- She was the mother of Antipater, who was executed in 4.

- The Hasmonaean princess Mariamme I: married 37, executed in 29/28. According to Flavius Josephus, Herod was passionately devoted to this woman, but she hated him just as passionately.

- Five children: Alexander, Aristobulus, a nameless son, Salampsio and Cyprus.

- An unknown niece: married 37. No children.

- An unknown cousin: married c.34/33. No children.

- The daughter of a Jerusalem priest named Simon, Mariamme II: married 29/28, divorced 7/6.

- They had a son named Herod.

- A Samarian woman named Malthace: married 28, died 5/4.

- A Jerusalem woman named Cleopatra: married 28.

- They had two sons named, Herod and Philip.

- Pallas: married 16.

- They had a son named Phasael.

- Phaedra: married 16.

- They had a daughter named Roxane.

- Elpis: married 16.

- They had a daughter named Salome.

The bitter end

Herod's reign ended in terror. When the king fell ill, two popular teachers, Judas and Matthias, incited their pupils to remove the golden eagle from the entrance of the Temple: after all, according to the Ten Commandments, it was a sin to make idols. The teachers and the pupils were burned alive. Some Jewish scholars had discovered that seventy-six generations had passed since the Creation, and there was a well-known prophecy that the Messiah was to deliver Israel from its foreign rulers in the seventy-seventh generation (more...). The story about the slaughter of infants of Bethlehem in the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew is not known from other sources, but it would have been totally in character for the later Herod to commit such an act.

A horrible disease (probably a cancer-like affection called Fournier's gangrene) made acute the problem of Herod's succession, and the result was factional strife in his family. Shortly before his death, Herod decided against his sons Aristobulus and Antipater, who were executed in 7 and 4 BCE, causing the emperor Augustus to joke that it was preferable to be Herod's pig (hus) than his son (huios) - a very insulting remark to any Jew.note

However, the emperor confirmed Herod's last will. After his death in 4 BCE, the kingdom was divided among his sons. Herod Antipas was to rule Galilee and the east bank of the Jordan as a tetrarch; Philip was to be tetrarch of the Golan heights in the north-east; and Archelaus became the ethnarch ("national leader") of Samaria and Judaea. Herod was buried in one of the fortresses he had built, Herodion. Few will have wept.

Literature

The most important ancient source for the rule of king Herod was written by Flavius Josephus: the Jewish War and the Jewish Antiquities. Both books are based on the history of Nicolaus of Damascus, king Herod's personal secretary.

Modern literature: Nikos Kokkinos, The Herodian Dynasty. Origins, Role in Society and Eclipse (1998 Sheffield) and D.W. Roller, The Building Program of Herod the Great (1998) supplement each other.