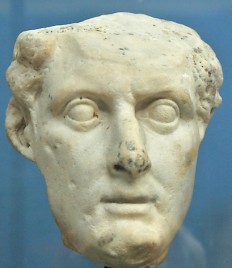

Ptolemy I Soter (3)

Ptolemy I Soter (367-282): friend and biographer of the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great, after his death king of Egypt, founder of the the Ptolemaic dynasty, one of the Diadochi.

King of Egypt

After the peace treaty of 311, the Diadochi started to prepare for the next round of war. Antigonus Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius tried to regain control of wealthy Babylonia, but were defeated by Seleucus in the Babylonian War. At the same time, Cassander of Macedonia, Lysimachus of Thrace, and Ptolemy of Egypt were trying to improve their positions. Ptolemy sent Ophellas to the far west, to join the tyrant of Syracuse, Agathocles, in an attempt to conquer Carthage. This expedition ended in disaster.

Ptolemy himself continued his conquest of Cyprus, strategically placed opposite the Phoenician coast. After his stay on the island in 309, he moved to the west, gaining influence in Pamphylia, Lycia, and Caria, and especially on the island of Cos at the entrance of the Aegean Sea. From there, Ptolemy sailed to Delos, where he reorganized the Nesiotic League, the confederacy of Aegean islands (308). For some time to come, the islanders would support him.

Yet, the Aegean expedition had been an error. Ptolemy had shown that he was interested in the Greek cities (he visited Corinth), which Cassander of Macedonia regarded as his backyard. Ptolemy understood that he had made a mistake and returned to Egypt. Not a moment too soon, because Antigonus was alarmed by Ptolemy's interference in Pamphylia, Lycia, and Caria, which were in his backyard. In 307, the Fourth Diadoch War started, in which Antigonus fought against an alliance of Ptolemy and Cassander.

At first, Antigonus was very successful, because his son Demetrius unexpectedly expelled Cassander's garrison from Athens, which forced the Macedonian leader out of the war for four years. He first had to restore order in Greece. In the spring of 306, Demetrius made an unopposed landing on Cyprus. It was was defended by Ptolemy's brother Menelaus, who was defeated and retired to the town Salamis, where Demetrius started to besiege him. After some time, Ptolemy arrived with a navy, and Demetrius found himself heavily outnumbered: he had some 15,000 men, Menelaus and Ptolemy commanded 27,000 soldiers. However, in a naval battle off Salamis, Demetrius crushed Ptolemy's fleet before it could join Menelaus' navy. His victory was total; Ptolemy did not even gather his men when he made his escape to Egypt. Seeing that he was chanceless, Menelaus surrendered. Cyprus was lost.

The consequence of the battle was that Antigonus was recognized as the most powerful ruler in the Greek world, and accepted the royal title. It was reasonable. After all, every descendant of Alexander the Great and his father Philip was by now dead, and it seemed that the empire was about to be reunited by a strong, new dynasty. Immediately, king Antigonus sent a diadem to his son.

When Lysimachus of Thrace and Seleucus of Babylonia heard the news, they accepted the royal title as well; only Cassander initially refused. Ptolemy assumed the royal diadem in the late summer of 306, and was crowned in the native fashion, as a pharaoh, in January 304. His throne name was the same as that of Alexander: Meriamun Setepenra ('beloved of Amun, Chosen by Ra'). Immediately, the first coins with his portrait were minted.

Presenting himself as pharaoh was the best way to obtain support from the native Egyptian population, support that Ptolemy desperately needed. His realms were defenseless now that he had lost his entire navy. Seizing the opportunity, Antigonus marched to Egypt with a very large army. He knew that Ptolemy was not completely defeated yet and also understood that he had to use as many soldiers as possible to ensure victory. The supplies were carried by his fleet, commanded by Demetrius. The plan was excellent, but the weather conditions were terrible: storms prevented the navy from approaching Egypt. Antigonus' army could no longer be fed and had to return. It had been a miraculous escape.

Although Antigonus and Demetrius had lost Egypt, they had kept the initiative in the war. Ptolemy was seriously weakened, Seleucus was occupied in the eastern satrapies, and Cassander was still restoring order in Greece. A new attack on Ptolemy seemed unwise and a war in the east was not Antigonus' priority; therefore he decided to attack Cassander. As a preparation, Demetrius had to besiege the isle of Rhodes, a mercantile republic that possessed a large navy and controlled the entrance to the Aegean Sea. If Rhodes fell, Antigonus and Demetrius could strike anywhere. Another reason to subdue the Rhodes was the fact that it could help Ptolemy rebuilding his navy, something that Antigonus wanted to prevent at all costs.

The siege started in 305 (text), but Rhodes was reinforced by Cassander and Lysimachus and especially Ptolemy. They all knew that as long as Rhodes withstood Demetrius, they were safe. The siege lasted long and ended in a compromise. The Rhodians promised that they would be loyal to Antigonus and Demetrius and would support them against all their enemies, except Ptolemy. In the propaganda of Antigonus, this was presented as a big victory, and Demetrius accepted the surname Poliorcetes, "taker of cities". Ptolemy also received an additional name: he was called Soter, the Savior. Thus ended the siege of Rhodes.

The compromise opened the road for Demetrius' invasion of Greece, which was to be the main theater of war in 304 and 303. Cassander came close to collapse, but when Lysimachus of Thrace, Seleucus of Babylonia, and Ptolemy understood that their enemies were almost ready to unite Macedonia with their Asian possessions, they decided to offer more help. Lysimachus unexpectedly invaded Asia Minor, which forced Antigonus to move to central Anatolia too. He also recalled Demetrius from Greece, and the two armies were able to pin down Lysimachus (302).

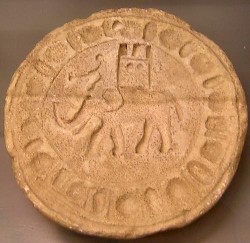

Immediately, Ptolemy announced to come to his assistance, and he invaded Syria, which he wanted to reconquer anyhow. However, an incorrect report that Antigonus had been victorious, made Ptolemy return home. Seleucus was less deterred, and marched with his Indian elephants from Babylonia to the west, where the decisive battle was fought at Ipsus (301). Antigonus was killed, his army was defeated, and Demetrius escaped with a small force.

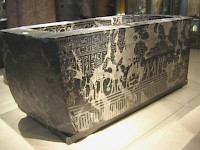

one of Ptolemy's ministers

The significance of the battle of Ipsus is that from now on, the unification of Alexander's empire was for once and for all impossible. Lysimachus took large parts of what is now Turkey and Seleucus received Syria, Phoenicia and Palestine, but discovered that parts had in the meantime been occupied by Ptolemy. Seleucus decided that it would be unkind to go to war against the man who had given him a chance to reconquer Babylonia. For the moment, this area remained quiet, but it was to be a bone of contention between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties in the third century.

So, in 300, a territorial agreement had been reached: Seleucus Asia, Lysimachus the eastern Aegean, Cassander Macedonia and Greece, and Ptolemy Egypt, Cyrenaica, and the coast of Syria. There was one complication, however: the navy of Demetrius, who now started a career as a pirate king. Cassander and Lysimachus had reason to fear the presence of the man in the region, and Ptolemy's Phoenicia lay dangerously exposed to his attacks. The three men concluded a treaty, which was in 300 confirmed by marriage: Ptolemy's daughter Arsinoe married Lysimachus, and Lysandra was given to Lysimachus' son Agathocles. Another reason for this alliance may have been Ptolemy's fear that Seleucus would try to drive him out of Phoenicia and Palestine. The new king of Asia was already showing his interest in this region by building new cities (like Seleucia and Antioch).

Seleucus had nothing to fear from Demetrius, but understood from the new alliance that Ptolemy was preparing for war. He now allied himself to Demetrius, married to his daughter Stratonice (299), and raided Samaria in Israel. Ptolemy was so impressed by Demetrius and Seleucus, that he accepted a treaty.

During the next years, Demetrius was trying to obtain a base in Greece and Macedonia, where he was eventually made king (294; text). He had to give up his more eastern possessions, and Ptolemy immediately seized Cyprus, Pamphylia, Lycia, and the Phoenician cities Sidon and Tyre. At the same time, he intensified his contacts with Athens.

In 288, the Macedonians revolted against their new king, and Demetrius, who suppressed it, decided to launch an all-out war on his eastern rivals. The reasons are poorly understood. There is evidence that Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus and king Pyrrhus of Epirus (a very close ally of Ptolemy) were already planning a war against Demetrius, and they may have been behind the Macedonian revolt. However this may be, in 287 Demetrius crossed the Aegean Sea, defeated his enemies, and was confronted with mutiny in his own army - the soldiers refused to go on. Demetrius was captured by Seleucus. Now, Lysimachus became king of Macedonia, and as he was now becoming too powerful, Seleucus attacked Lysimachus, conquered Asia Minor, defeated his opponent at Corupedium, and crossed into Europe (281).

While these confused developments were taking place in the north, Ptolemy just watched and did nothing. There was no reason to intervene now that his rivals were butchering themselves. Consequently, the king of Egypt is almost absent from our sources and we know not much about Ptolemy's policy in the 280s. It is likely that he began to organize the Museum and Library of Alexandria, projects that were already in full progress during the reign of Ptolemy's son Ptolemy II Philadelphos, and must have been initiated by his father.

Another important act was Ptolemy's appointment of Philadelphos as his successor. This was an important step, because there was another contender, also named Ptolemy (and later surnamed Keraunos). As we have already seen above, Ptolemy had married Antipater's daughter Eurydice in 321; she had given birth to Ptolemy Keraunos, who was the first in line of succession. However, Ptolemy I Soter had also married a lady named Berenice, who was the mother of Ptolemy Philadelphos. Why Ptolemy preferred the younger son is not fully understood. Keraunos did not accept this treatment, went to the court of Seleucus, and accompanied his protector during his war against Lysimachus.

In 285, Ptolemy I Soter accepted Ptolemy II Philadelphos as his co-ruler. In January 282, the founder of the Ptolemaic Empire died, and his son became sole ruler. The second Ptolemy started his reign in an exciting period, because the war between Lysimachus and Seleucus had now started. In 281, after the battle of Corupedium, Seleucus seemed to unite Asia and Europe, and the new Egyptian king may have terrified, because Seleucus would of course demand that Egypt would return to the reunited and restored Macedonian empire.

However, things were to move in altogether different direction. Seleucus went to Macedonia, and was unexpectedly killed by the elder Ptolemy: because of this incident, he was called Keraunos ("thunderbolt"). Immediately, there were big problems in the kingdom that Seleucus had left behind, and Keraunos became king of the European part. In Asia, Seleucus was succeeded by his son Antiochus. In this confusion, Ptolemy II overran many Seleucid possessions in Cilicia, Pamphylia, Lycia, and Caria. The Ptolemaic Empire, which had been threatened in 281, was all-powerful in 279, and was to last for more than two centuries.