Germania Inferior (12)

Q152136Germania inferior: small province of the Roman empire, situated along the Lower Rhine. Its capital was Cologne.

The language boundary

As we have seen at the end of the preceding part of this article, the Franks invaded Germania Secunda in 355. General Julianus, the future emperor, defeated them and allowed them to remain as peasants in what is now called Brabant, but was once known as Toxandria. From now on, the country between Tongeren and the lower Meuse was repopulated by Germanic immigrants from the north, who could settle anywhere they wanted, provided that they were loyal to the Roman authorities and did not venture south of the main road from Boulogne to Bavay, Tongeren, and Cologne.

Now, the Franks became the most important ethnic group in the region. Their take-over of the country is illustrated by the villa at Voerendaal: it was still functioning in the fourth century, and the owner allowed several Germanic families to build houses on his grounds. Probably, the immigrants were working on the farm. After 355, they were the only remaining people, and the farm had peacefully changed from a large villa into a small Frankish village. There must have been many settlements with similar histories.

Although the change was gradual and peaceful, and did not imply the end of the military settlements, the Roman government was worried. In 365, marriage between citizens and immigrants was forbidden, although it is hard to believe that this ban was ever applied.

Many Franks served in the Roman armies. The frontier guards at Nijmegen and the cavalrymen at Tournai all had Germanic ancestors. Some of them became really influential, like the Frank Arbogast, who was supreme commander of the Roman forces in western Europe between c.385 and 394. Obviously, the central government in Italy did not think that this man was a barbarian, and indeed, Arbogast remained loyal to the empire.

Most Franks, however, retained their native culture and still spoke their Germanic dialect. Toxandria was now lost for the Latin language. This can be illustrated by a well-known example: in the fourth century the sound /k + vowel/ became /sh + vowel/. Toponyms south of the line Boulogne - Bavay - Tongeren - Cologne changed accordingly, but the linguistic change did not take place in Toxandria. In the south, the common name castra ('fortress') became Chestres or Château, in the north we can still find names like Kesteren and Kaster. In this way, the language boundary between Dutch and French that tragically divides the Low Countries until the present day, was created in the second half of the fourth century.

It is no coincidence that the language boundary is situated where it is. The road between Boulogne and Cologne was important to the Romans, because to the south were the fertile loessial soils, where grain was produced. Because they wanted to keep this zone, the road was heavily defended. There were big differences between the north and south. In the Latin part of the Low Countries, the old commercial villa economy was still functioning and merchants imported Mediterranean products. The owners of the villas were rich people who played an important role in public life. Cavalry units were stationed in the towns. In the north, we find nothing of this kind. The Romans still guarded the Rhine, but the region between this first line of defense and the second line (Boulogne-Cologne) was forever lost for the Mediterranean civilization. The language boundary marked a cultural division as well. And this division had a religious dimension as well.

Christianity

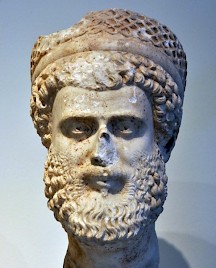

Constantine I the Great (r.306-337) brought the system of defense in depth to perfection. However, he is best known for his conversion to Christianity. Earlier emperors had persecuted the adherents of the new faith, but Constantine, who invaded Italy in 312 and attributed his victory to divine guidance (and the assistance of many soldiers from Tongeren and Deutz), started to support the church.

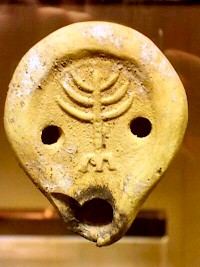

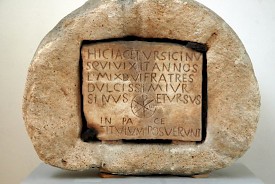

Many people now converted and were baptized. Several archaeological finds prove that Christianity swiftly gained ground in the Low Countries. For example oil lamps with Christian symbols (e.g., cross), seals with anchor and fishes, and helmets with a Christogram (☧). Several inscriptions refer to Christian beliefs, like the tombstone of a lady named Meteriola. Another remarkable aspect of the Christianization is the custom to turn the sockles of Jupiter columns upside down and use them as altars.

Ecclesiastical sources inform us about the first Christian leaders of Germania Secunda. The first one is Maternus of Cologne, a native of Trier, the residence of Maximianus (285-305). Because this emperor actively persecuted the Christians, Maternus moved to Cologne, where he was elected bishop. In 313, after the conversion of Constantine I the Great, he attended the Council of Arles, which proves that he was a rich man (otherwise, he would have been unable to make the trip).

Servatius of Tongeren belonged to the next generation and was a contemporary of the famous Martin of Tours. Servatius must have been a rich man too, because in 343 he attended the Council of Serdica, served as a diplomat in Syria (350), and spoke at the Council of Rimini in 359. In his hometown, he dedicated a church to Our Lady. (The remains have been discovered under the present basilica.) For unknown reasons, he settled in Maastricht at the end of his life, where he died in 384. His tomb can still be visited in the basilica of Sint-Servaas.

People like Maternus and Servatius were influential and played an important role in public life. Their contemporaries Martin of Tours and Ambrose of Mailand sometimes quarreled with emperors. In the second half of the fourth century, the church was becoming very powerful.