Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire: the continuation of the Roman Empire in the Greek-speaking, eastern part of the Mediterranean. Christian in nature, it was perennially at war with the Muslims. It flourished during the reign of the Macedonian emperors; its demise was the consequence of attacks by Seljuk Turks, Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks.

Byzantium was the name of a small, but important town at the Bosphorus, the strait which connects the Sea of Marmara and the Aegean to the Black Sea, and separates the continents of Europe and Asia. In Greek times the town was at the frontier between the Greek and the Persian world. In the fourth century BCE, Alexander the Great made both worlds part of his hellenistic universe, and later Byzantium became a town of growing importance within the Roman Empire.

By the third century CE, the Romans had many thousands of miles of border to defend. Growing pressure caused a crisis, especially in the Danube/Balkan area, where the Goths violated the borders. In the East, the Sasanian Persians transgressed the frontiers along the Euphrates and Tigris. The emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) was one of the first to realize the impossibility of managing the empire's problems from distant Rome.

Constantinople

So, in 330 Constantine decided to make Byzantium, which he had refounded a couple of years before and named after himself, his new residence. Constantinople lay halfway between the Balkan and the Euphrates, and not too far from the immense wealth and manpower of Asia Minor, the vital part of the empire.

"Byzantium" was to become the name for the East-Roman Empire. After the death of Constantine, in an attempt to overcome the growing military and administrative problem, the Roman Empire was divided into an eastern and a western part. The western part is considered as definitely finished by the year 476, when its last ruler was dethroned and a military leader, Odoacer, took power.

Christianity

In the course of the fourth century, the Roman world became increasingly Christian, and the Byzantine Empire was certainly a Christian state. It was the first empire in the world to be founded not only on worldly power, but also on the autority of the Church. Paganism, however, stayed an important source of inspiration for many people during the first centuries of the Byzantine Empire.

When Christianity became organized, the Church was led by five patriarchs, who resided in Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, Constantinople, and Rome. The Council of Chalcedon (451) decided that the patriarch of Constantinopel was to be the second in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Only the pope in Rome was his superior. After the Great Schism of 1054 the eastern (Orthodox) church separated form the western (Roman Catholic) church. The centre of influence of the orthodox churches later shifted to Moscow.

Cultural Life

Since the age of the great historian Edward Gibbon, the Byzantine Empire has a reputation of stagnation, great luxury and corruption. Most surely the emperors in Constantinopel held an eastern court. That means courtlife was ruled by a very formal hierarchy. There were all kinds of political intrigues between factions. However, the image of a luxury-addicted, conspiring, decadent court with treacherous empresses and an inert state system is historically inaccurate. On the contrary: for its age, the Byzantine Empire was quite modern. Its tax system and administration were so efficient that the empire survived more than a thousand years.

The culture of Byzantium was rich and affluent, while science and technology also flourished. Old literary genres were practiced again: the art of epistolography is just one exemple (e.g., Aristaenetus).

Very important for us, nowadays, was the Byzantine tradition of rhetoric and public debate. Philosophical and theological discources were important in public life, even emperors taking part in them. The debates kept knowledge and admiration for the Greek philosophical and scientific heritage alive. Byzantine intellectuals quoted their classical predecessors with great respect, even though they had not been Christians. And although it was the Byzantine emperor Justinian who closed Plato's famous Academy of Athens in 529, the Byzantines are also responsible for much of the passing on of the Greek legacy to the Muslims, who later helped Europe to explore this knowledge again and so stood at the beginning of European Renaissance.

History: Justinian

Byzantine history goes from the founding of Constantinople as imperial residence on 11 May 330 until 29 May 1453, when the Ottoman sultan Memhet II conquered the city. Most times the history of the Empire is divided in three periods.

The first of these, from 330 till 867, saw the creation and survival of a powerful empire. During the reign of Justinian (527-565), a last attempt was made to reconquer provinces of the former Roman Empire under one ruler, the one in Constantinople. This plan largely succeeded: the wealthy provinces in Italy and Africa were reconquered, Libya was rejuvenated, and money bought sufficient diplomatic influence in the realms of the Frankish rulers in Gaul and the Visigothic dynasty in Spain. The refound unity was celebrated with the construction of the church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, in Constantinople. The price for the reunion, however, was high. Justinian had to pay off the Sasanian Persians, and had to deal with firm resistance, for instance in Italy.

Under Justinian, the lawyer Tribonian (500-547) created the famous Corpus Iuris. The Code of Justinian, a compilation of all the imperial laws, was published in 529; soon the Institutions (a handbook) and the Digests (fifty books of jurisprudence), were added. The project was completed with some additional laws, the Novellae. The achievement becomes even more impressive when we realize that Tribonian was temporarily relieved of his function during the Nika riots of 532, which in the end weakened the position of patricians and senators in the government, and strengthened the position of the emperor and his wife.

After Justinian, the Byzantine and Sasanian empires suffered heavy losses in a terrible war. The troops of the Persian king Khusrau II captured Antioch and Damascus, stole the True Cross from Jerusalem, occupied Alexandria, and even reached the Bosphorus. In the end, the Byzantine armies were victorious under the emperor Heraclius (r.610-642).

However, the empire was weakened and soon lost Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Cyrenaica, and Africa to the Arabs. For a moment, Syracuse on Sicily served as imperial residence. At the same time, parts of Italy were conquered by the Langobards, while Bulgars settled south of the Danube. The ultimate humiliation took place in 800, when the leader of the Frankish barbarians in the West, Charlemagne, preposterously claimed that he, and not the ruler in Constantinople, was the Christian emperor.

History: the Macedonian Dynasty

The second period in Byzantine history consists of its apogee. It fell during the Macedonian dynasty (867-1057). After an age of contraction, the empire expanded again and in the end, almost every Christian city in the East was within the empire's borders. On the other hand, wealthy Egypt and large parts of Syria were forever lost, and Jerusalem was not reconquered.

In 1014 the mighty Bulgarian empire, which had once been a very serious threat to the Byzantine state, was finally overcome after a bloody war, and became part of the Byzantine Empire. The victorious emperor, Basilius II, was surnamed Boulgaroktonos, "slayer of Bulgars". The northern border now was finally secured and the empire flourished.

Throughout this whole period the Byzantine currency, the nomisma, was the leading currency in the Mediterranean world. It was a stabil currency ever since the founding of Constantinopel. Its importance shows how important Byzantium was in economics and finance.

Constantinople was the city where people of every religion and nationality lived next to one another, all in their own quarters and with their own social structures. Taxes for foreign traders were just the same as for the inhabitants. This was unique in the world of the middle ages.

History: Crisis

Despite these favorable conditions, Italian cities like Venice and Amalfi, gradually gained influence and became serious competititors. Trade in the Byzantine world was no longer the monopoly of the Byzantines themselves. Fuel was added to these beginning trade conflicts when the pope and patriarch of Constantinople went separate ways in 1054 (the Great Schism). Another problem was the rise of Byzantine aristocratic families, which were usually unwilling to submit their private interest to the interest of the commonwealth.

Decay became inevitable after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Here, the Byzantine army under the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes, although reinforced by Frankish mercenaries, was beaten by an army of the Seljuk Turks, commanded by Alp Arslan ("the Lion"). Romanus was probably betrayed by one of his own generals, Joseph Tarchaniotes, and by his nephew Andronicus Ducas.

After the battle, the Byzantine Empire lost Antioch, Aleppo, and Manzikert, and within years, the whole of Asia Minor was overrun by Turks. From now on, the empire was to suffer from manpower shortage almost permanantly. In this crisis, a new dynasty, the Comnenes, came to power. To obtain new Frankish mercenaries, emperor Alexius sent a request for help to pope Urban II, who responded by summoning the western world for the Crusades. The western warriors swore loyalty to the emperor, reconquered parts of Anatolia, but kept Antioch, Edessa, and the Holy Land for themselves.

History: Decline and Fall

For the Byzantines, it was increasingly difficult to contain the westerners. They were not only fanatic warriors, but also shrewd traders. In the twelfth century, the Byzantines created a system of diplomacy in which deals were concluded with towns like Venice that secured trade by offering favorable positions to merchants of friendly cities.

Soon, the Italians were everywhere, and they were not always willing to accept that the Byzantines had a different faith. In the age of the Crusades, the Greek Orthodox Church could become a target of violence too. So it could happen that Crusaders plundered the Constantinople in 1204. Much of the loot can still be seen in the church of San Marco in Venice.

For more than half a century, the empire was ruled by monarchs from the West, but they never succeeded in gaining full control. Local rulers continued the Byzantine traditions, like the grandiloquently named "emperors" of the Anatolian mini-states surrounding Trapezus, where the Comnenes continued to rule, and Nicaea, which was ruled by the Palaiologan dynasty.

The Seljuk Turks, who are also known as the Sultanate of Rum, benefited greatly of the division of the Byzantine Empire, and initially strengthened their positions. Their defeat, in 1243, in a war against the Mongols, prevented them from adding Nicaea and Trapezus as well. Consequently, the two Byzantine mini-states managed to survive.

The Palaiologans even managed to capture Constantinople in 1261, but the Byzantine Empire was now in decline. It kept losing territory, until finally the Ottoman Empire (which had replaced the Sultanate of Rum) under Mehmet II conquered Constantinopel in 1453 and took over government. Trapezus surrendered eight years later.

Artistic Legacy

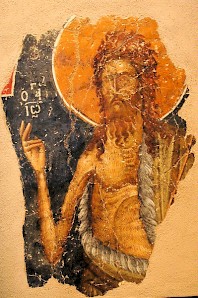

After the Ottoman take-over, many Byzantine artists and scholars fled to the West, taking with them precious manuscripts. They were not the first ones. Already in the fourteenth century, Byzantine artisans, abandoning the declining cultural life of Constantinople, had found ready employ in Italy. Their work was greatly appreciated and western artist were ready to copy their art. One of the most striking examples of Byzantine influence is to be seen in the work of the painter Giotto, one of the important Italian artists of the early Renaissance.

Byzantine lamp from Syria |

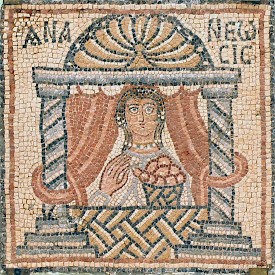

Byzantine weight |

Byzantine funerary stele from Egypt |

Byzantine horse-shaped lamp |